The Kerry Plan

Some say it was a mistake, but if it was then it was the “gaffe heard round the world.” John Kerry made a sarcastic, and possibly off-the-cuff, comment about how Syrian President Bashar al Assad might escape U.S. military attacks aimed at punishing him for using chemical weapons on August 21st:

He could turn over every single bit of his chemical weapons to the international community in the next week. Turn it over, all of it, without delay, and allow a full and total accounting for that. But he isn’t about to do it, and it can’t be done, obviously.

Within what seemed like moments, Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, endorsed a plan to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles, and pledged Russia’s support in the process. Soon after, Syria Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem expressed that the Assad regime was willing to work with the Russians. With three sentences, John Kerry appears to have altered the international community’s entire conversation and trajectory with regards to Syrian intervention.

As this story is developing, there will be rolling updates. For instance, Syria has suggested that it is willing to sign the Chemical Weapons Convention, a 20 year old international agreement that only Syria and four other states have refused to sign thus far. France has stated that it will draft UN Security Council resolution that would put in place verification methods in order to ensure that Syria carries through with its pledge. Sensing that Russia and Assad were trying to derail US efforts to build a military coalition to strike Syria, France’s proposal included language that could open the door for international strikes against Syria should it fail to comply. Russia has threatened to veto the UNSC resolution.

John Kerry spoke on a Google Hangout, and he has reiterated that the White House is interested in this proposal, but there have to be verification processes built into any agreement, and he and the President are unwilling to wait a long period of time for the plan to be worked out. Obama’s speech suggested that the United States is still interested in moving forward with military intervention, but it was willing to briefly give the diplomatic process to work. In the end, though, he would need strong language that ensured that Assad was held accountable for destroying the CW. And again, Russia has said that it is unwilling to accept those kinds of preconditions.

In other words, the so-called “Kerry Plan” to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons appears to already be falling apart. Just moments ago, the UNSC meeting was postponed (reportedly by Russia).

There are also a lot of concerns about the feasibility of the plan should an agreement be signed.

For the moment, however, let’s just go on the assumption that world powers did agree to a deal that would put Russia in charge of ensuring that the Assad regime disposed of its weapons. Can either the Putin administration or the Assad regime be trusted to abide by any agreements they make with the international community? Let’s look at recent history to find out.

Russia Blocks International Progress as Assad’s Crimes Grow

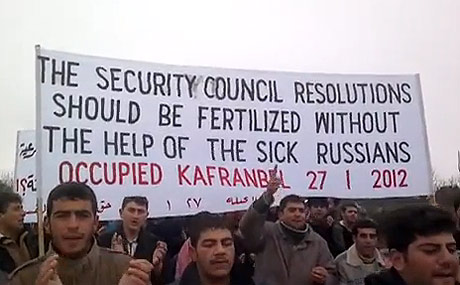

First, Russia has blocked nearly every UN Security Council resolution, and all of the ones that would hold Assad accountable for his actions. In October of 2011 Russia vetoed the first resolution which would have condemned Assad’s use of violence against protests. At this point, the Syrian crisis was in its simplest form. Not only where there no Al Qaeda aligned rebel groups, there were hardly any rebel groups at all. The rebellion was only starting, and was made up almost entirely of Assad’s own defectors, men who were fleeing for their lives after they refused to kill unarmed protesters. This was, in many ways, the moment where Russia lost its best chance to help end the crisis. At this point it was clear that Assad could not return Syria to the status quo through force, but things had not yet decayed to the point where a transitional government was unthinkable.

Russia did, however, back an option, in April 2012 – the launch of the Kofi Annan plan. Annan believed that he could find a political solution to the Syrian crisis.

However, thanks in part to Russian and Chinese obstructionism, the best chance for a political solution had already been lost. On two occasions, the Assad regime had agreed to cooperate with the demands of the Arab League, which wanted to oversee a ceasefire in order to alleviate the humanitarian crisis and foster a political solution. On those occasions, Assad proved that he could not be trusted by failing to meet every single demand that he had agreed to. And Russia proved that it was more interested in watching Assad’s back than in fostering a solution to the Syrian crisis.

Assad agrees to withdraw troops, then launches the siege of Homs

In early November of 2011, Assad told the Arab League that he would withdraw tanks and troops from all of his cities, and he would allow peaceful protests to take place. Over the next week, however (each word is a separate link), starting as soon as the words came out of his mouth, not only did Assad continue to kill dozens of civilians, he moved more tanks and artillery into places like Homs (and Daraa and Hama, where there was no insurgency yet), and began to wage what looked like an all out war against his own populace. In fact, this was the beginning of the assault against Homs which remains some of most intense violence that the war has seen to date.

In December, the Arab League negotiated their second settlement with the regime when Assad agreed to pull its tanks out of Syrian cities in order to allow observers to visit the scenes. Arab League Observers pushed into Syrian cities only to find that Assad’s troops and tanks were still deployed, and the fighting had never stopped. By January, it was clear that no part of Assad’s promise had been kept, and by February the full brunt of Assad’s tanks an artillery had flattened huge swaths of Homs, one of Syria’s largest and oldest cities, leaving about two thousand dead (the VDC, an interactive database that verifies death tolls, reports that 1853 people were killed in Homs between November 2011 and February 2012 – their database is one of the most conservative with regards to death tolls). Before the siege of Homs, it was rare to hear about daily casualty tolls reaching more than one or two dozen. Since then, the daily death toll has been exponentially higher.

The Assad regime claimed at the time that it had withdrawn its armed forces from every location except in areas where counter-terrorism operations were being enforced, and so it was in full compliance with the Arab League agreement. In reality it had unleashed its fully fury on Homs, and had increased its crackdown in Daraa, Idlib, and elsewhere.

This was the point where even the most conciliatory members of the opposition began to realize that Assad could never be trusted. This was the point where even many opposition groups that had been committed to peaceful change realized that an insurgency, or foreign intervention, were the only way out of this crisis.

Russia Backs its “Historical Friends”

What did Russia do during this critical period in the history of the Syrian conflict? On November 2nd, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that he supported the Arab League initiative, but then he blamed outside forces for provoking the escalation of the conflict by arming “extremists.” It’s noteworthy that there is no evidence that this early on there were a significant amount of weapons coming from outside of Syria, except for the arms that Russia was supplying the regime. In fact, this early on in the conflict, the vast majority of rebels were defectors. It was the siege of Homs between November and February that changed this.

Then Lavrov went on to give us our key sentence – why is Russia concerned with Syria? Here was his answer:

“We are very concerned about the fate of this region because we have a lot of friends there with whom we have maintained close and warm relations for decades, with some of them – for centuries. With many countries in the region we have much in common in terms of history, culture and traditions. This is one reason why we cannot ignore what is happening there.”

Within days, it was clear to the few who could consider themselves Syrian watchers at the time that the Arab League agreement was broken by the regime before it had even started. As the violence intensified, Russia’s Foreign Ministry made no reference to the Arab League agreement or Assad’s assaults against his own cities. Instead, on the 15th of November, Lavrov met with leader of the opposition’s Syrian National Council (SNC), Burhan Ghalioun, and pledged Russia’s commitment to peace through working to broker a deal between both sides.

With things continuing to decay, on November 17th, Russian lawmaker Konstantin Kosachev said that Russia was perhaps the only country working with both the regime and the opposition, but then he blamed the escalation of violence on extremists who were being backed by foreign powers. He said that the Syrian people were mistaken if they thought that violence could bring them freedom, as if he were asserting that it was the Syrian people, not the Assad regime, that started the fight. And while Syrian rebels in Homs, a growing number of whom were civilians who were tired of their neighborhoods being shelled, were struggling to find bullets for their AK-47s, Kosachev said that it was the rebels who were using heavy weapons, and the war was the result of the Assad regime trying to defend itself.

By November 21st, with the violence continuing to escalate, Lavrov made this statement blaming the West for the violence:

“In Syria we are now seeing a situation where the Arab League is calling for a halt to violence and the beginning of dialogue, and western countries and the capitals of some countries in the region are making calls to the contrary, expressly recommending the opposition hold no talks with the Assad regime,” Lavrov announced. “It looks like a political provocation on an international scale. Yes, violence has to be stopped, but this demand has to be addressed to the authorities and armed groups in the Syrian opposition,” he argued.

On November 28th, Russia sent warships to defend its base in the regime stronghold of Tartus. On November 29th, Russia spoke out against an arms embargo in Syria, and said that they opposed given the Assad regime an ultimatum. On December 1st, Russia announced that it would not stop supplying the Assad regime with weapons. On December 8th Lavrov said that the world needed to be patient with Syria.

But by December, the death toll was skyrocketing in Homs, the crackdown against protesting civilians continued to intensify in every corner of the country, the Russian government and the Assad regime showed no signs of willingness to compromise, and the insurgency was exploding all across Syria as a result. It’s worth noting that around this time there were some of the earliest reliable reports of extremism in the ranks of rebel fighters – extremism that was born in Homs before it spread elsewhere.

In February, Russia used its veto power for a second time, stopping a UNSC draft resolution that even stipulated than nothing in the resolution could be used as justification of military action. In other words, even with the threat of international military intervention taken off the table, Russia blocked the resolution and covered Assad’s back.

The Crisis Deepens, and Russia Finally Commits to a Dead Idea

There was, as I mentioned, one time where Russia did not block a UNSC resolution. By April 2012, the situation on the ground was changing somewhat. The pounding of Homs did not lead to the surrender of the insurgency. Instead, between December 2011 and March of 2012, the “Free Syrian Army” had begun to actually fully liberate several towns. First to be fully liberated was Zabadany, a suburb of Damascus. Kafer Takharim, a mountain town in Idlib province, was next. Over the next few months the regime began to retake some of the territory it was losing, but the violence in Homs had cost the regime militarily, all the while it had sparked a rise in defections and civilian conscripts who were joining the ranks of the rebellion. The insurgency was now growing so quickly, as were the death tolls, that it was become clear to everyone that the opportunity to end the conflict diplomatically was passing. In fact, it had likely already passed [1. Read a history of the Syrian insurgency between the start of the Arab Uprisings and July 2012.].

Because of the Arab League incidents, by the time the Kofi Annan plan had surfaced in April, Assad and Russia had lost all credibility. Several local ceasefires had decayed to nothing. With each pledge from the regime to stop violence and find a solution, new weapons were introduced onto Syria’s battlefields. Kofi Annan and the United Nations, not knowing what else to do, settled on a non-binding approach that would send UN delegations into Syria to try to broker a peace. The rebels, now increasingly confident that the vast majority of Syrians supported them and they could eventually win a military victory, were now hesitant to stop their offensives unless the regime stood down first. After all, previous stand-downs and ceasefires had been broken by regime sneak attacks.

In July 2012, the Geneva Convention sought to modify the Annan plan to give it more teeth. As I explained in a separate analysis, the plan would have pushed for the formation of a transitional government. However, the rest of the world realized that any transitional process that was being led by the Assad regime would be a farce (and not “transitional” by definition). Thus the United States and others, echoing the calls from the Syrian opposition leadership that would need to be onboard with any plan, called for the exclusion of Assad from a transitional government — a call that the Russian government rejected. This did not, however, stop Sergei Lavrov from describing the Geneva agreement as the “Russian-American Initiative,” a title that couldn’t be more misleading.

The Annan plan had little chance of success from the start, but by August 2012 the futility of the mission was clear to even Kofi Annan, who quit the process in frustration.

Why would Russia commit to a dead idea? Russia has always insisted that it will not accept any preconditions, most especially those that required the Assad to resign. Though Russia likely would have liked to have seen a political settlement, they were unwilling to foster one where Assad was not in control of the transition. And if the Russian government was ever frustrated at its ally and trading partner, it never showed it publicly. The Annan plan was so watered down that it stood nearly no chance of leading to a transitional government that would ouster it’s “historical friends.”

Will This Be Any Different?

The UN is now hopelessly deadlocked on Syria. Russia and China have repeatedly blocked binding resolutions at every turn. It’s increasingly clear that the West will not sign on to any plan that would destroy Assad’s chemical arsenal without significant supervision of the process, to say nothing of peacekeepers to ensure that the weapons do not fall into the wrong hands, and a binding resolution that would hold Assad accountable for his actions should he fail to surrender the entire stockpile. Russia and China will block such measures.

To be clear, in order to destroy this many chemical munitions, it would take years, billions of dollars, and a significant peacekeeping force. It took the United States more than 25 years to destroy its own arsenal, and Russia is just over halway through with its own dismantling project. Then there is the situation on the ground in Syria. Assad’s largest chemical weapons base, and possibly the largest single CW stockpile in the world, has been virtually surrounded by jihadist rebels for more than six months. While jihadists still make up a small portion of the rebel ranks, a disproportionately large percentage of fighters near the Al Safeera base are jihadists — perhaps for obvious reasons.

Russia won’t agree to this. Assad won’t agree to this. But if one understands the history of how Assad has broken his promises and Russia has refused to hold him accountable, one might actually be more concerned about what would happen if they agree to the plan.