Fontanka, an independent Saint Petersburg newspaper, has published an investigation into the activities and deaths of Russian “private military contractors” (PMCs) in Syria and Ukraine.

The paper studied a group known as ChVK (PMC) Wagner, formed out of the remnants of the “Slavonic Corps,” a mercenary unit that fought ignominiously in Syria in 2013.

While Fontanka, which first reported on the Slavonic Corps debacle that year, recently reported that members of that unit had returned to Syria, it was not until today that anyone claimed to have documentary evidence of the Wagner group’s operations.

Fontanka profiles several fighters with the unit and charts their activities from training centers in Russia to Ukraine’s Lugansk Region and the Syrian town of Palmyra.

At the center of the group is 46-year-old Dmitry Utkin, a lieutenant colonel who finished his professional service in the 700th Independent Spetsnaz Detachment of the 2nd Independent Brigade of the GRU (military intelligence) in 2013. Utkin then went to work for the Moran Security Group, a shady, Moscow-based PMC whose offshore ownership structure leads to Belize and the British Virgin Islands.

Utkin survived the disastrous Slavonic Corps mission to Syria in the fall of 2013 and reappeared in Ukraine’s Lugansk region in 2014.

An aficionado, as Fontanka puts it, of the aesthetics and ideology of the Third Reich, Utkin assumed the nom de guerre of Wagner in tribute to Hitler’s favourite composer, and became the commander of his own, eponymous unit. In Lugansk, he was known for eschewing a modern Russian battle helmet for a Second World War Wehrmacht coal-scuttle type.

This is the only photo Fontanka could find of Utkin:

Despite reports of his death in January this year, Fontanka reports that he is alive and well, either in Syria or at the Wagner ChVK training camp in Molkino, in Russia’s Krasnodar Krai.

Bearing in mind that Utkin is still in the GRU reserves, and so not truly retired, it is worth noting that Molkino is home to the base of the GRU 10th Independent Special Forces Brigade.

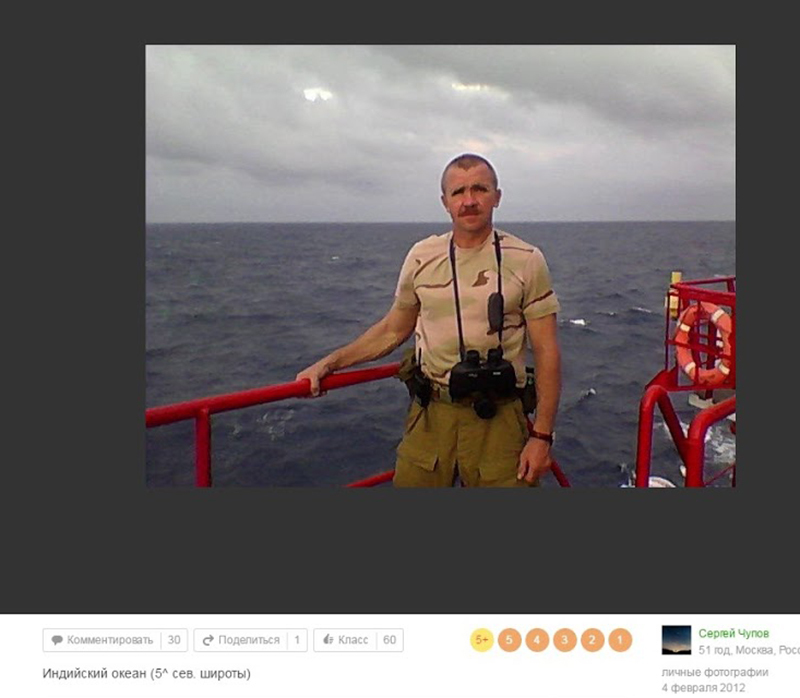

Another key member of the unit, 51-year-old Sergei Chupov, known as Chub, was killed near Damascus earlier this year.

As we reported last week, Chupov’s death was investigated by RBK and the Conflict Intelligence Team, a group of Russian bloggers and military experts, who reported that he had served in the Interior Ministry’s Internal Troops and fought in both Afghanistan and Chechnya.

CIT Reports 6th Russian Soldier's Death in Syria But Widow, Army and Kremlin Denyhttps://t.co/AGXheZHpkE pic.twitter.com/lknxKjEuOI

— The Interpreter (@Interpreter_Mag) March 23, 2016

One source told the investigators that Chupov had retired from active service in the mid-2000s, and indeed, Fontanka reports today that he left the Internal Troops at the end of the 90s. Chupov was then one of the founding members of ChVK Wagner, flying in May 2014 to the Russian border region of Rostov with Utkin and group of veteran instructors. Almost all of the group of instructors, bar Chupov, had worked for the Moran Security Group.

Chupov and the other instructors then trained the new unit at a camp near the village of Vesyoly, around 100 kilometers from the Ukrainian border.

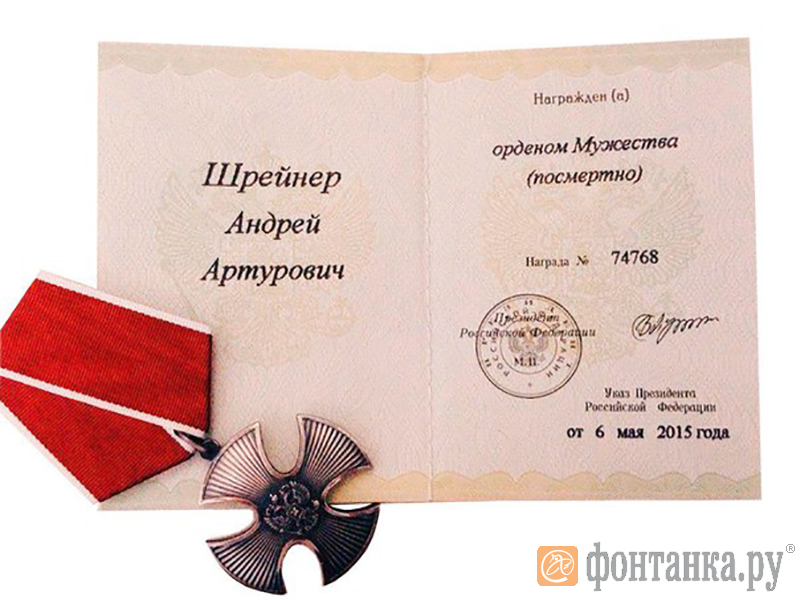

According to Fontanka, the only documentary evidence of the existence of ChVK Wagner comes in the striking form of documents signed by President Vladimir Putin himself.

Wagner fighters were awarded medals for bravery and courage, some posthumously, for their actions in both Ukraine and Syria.

One veteran of the unit told Fontanka that there had been two visits, on February 23 and May 9, to the Molkino base by an unidentified man, allegedly a member of the intelligence services with a rank of no less than General-Major.

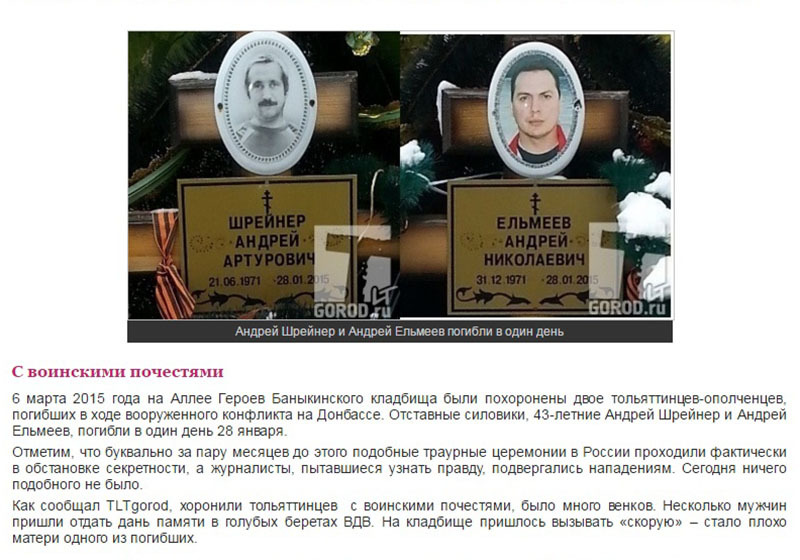

Two men posthumously honored were Andrei Yelmeyev and Andrei Shreiner. Both were buried on March 6, 2015, in Togliatti. Both were 43 years old and both were reportedly killed on January 28, 2015. A local news site reported that they had been killed fighting with separatist militias in Ukraine

But Fontanka reports that while both were indeed killed in the battle for Debaltsevo, neither of the men were fighting with the separatist militias or the Russian regular forces. Both names in fact appeared on the lists of those awarded the Order of Courage for their service in ChVK Wagner on May 9, 2015.

Another fighter awarded both the medal for bravery and the Order of Courage was 38-year-old Maksim Kolganov, a Don Cossack killed on February 3 this year.

While posts on a Don Cossack Internet forum stated that Kolganov had been killed performing military duties on that date, they did not specify where.

Fontanka learned, however, that Kolganov had been in Latakia, Syria, where he acted as the gunner in a BMP (infantry fighting vehicle) crew. Comrades of the deceased man shared some photos:

Kolganov’s medals were placed on a pillow beside his coffin:

Fontanka also asked veterans of the Wagner unit to comment on photos released by ISIS, purportedly taken from the body of a Russian fighter, killed with three others, in a battle near Palmyra this month.

Despite ‘Withdrawal’ Russians Continue To Fight And Die In Syria https://t.co/Y5NoHNPBSa pic.twitter.com/E0D9MfPQ09

— The Interpreter (@Interpreter_Mag) March 23, 2016

One of the men in the photos was identified as a fighter with the call-sign ‘Shlang,’ who was killed in December last year by an anti-personnel mine.

Shlang is one of the men in the photo below, which Fontanka‘s experts have identified as being taken in the Summer of 2014 in the Starobeshevo area of Ukraine’s Donetsk region:

That ISIS has produced photos taken in Ukraine from a phone seized in Syria suggests that fighters from Wagner, or at least another unit, be it mercenary or regular, were indeed killed near Palmyra.

The others could not be identified, but the veterans did recognize the bunk beds in the photos as those of ChVK Wagner’s housing block near Damascus.

Shockingly, while the death of only six Russian servicemen in Syria has been officially acknowledged, Fontanka’s sources reported dozens of losses in ChVK Wagner. Of a company of 93 men sent to Syria in September last year, only a third returned without injury in December, says one of the survivors.

Secrecy is maintained as many fighters in the group do not even know the first names, let alone the surnames of their platoon comrades. “Curiosity is not welcomed,” said one fighter.

Not all of the men in the unit are Russian. One platoon is formed of Serbs, led by Davor Savicic, a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina and old comrade of Utkin’s who fought in the Slavonic Corps. Savicic was convicted and sentenced to 20 years for involvement in a bombing in Bosnia in 2001. The conviction was subsequently overturned on technical grounds, however.

The unit is surprisingly large. A former fighter with the group responded when Fontanka asked him if there were around 250-300 fighters in the mercenary force:

“Are you kidding? Think about it. Three reconnaissance-assault companies, each with ninety to a hundred men. Three platoons with recoilless rifles and automatic grenade launchers – a fire support company. An air defense company with Iglas. A communications company. Guard company. The medical unit. Plus civilian service personnel. Without civilians – six hundred people.”

The high loss rate in the group can be explained by what the former fighters describe as World-War-Two-style tactics.

“It’s right out of the Second World War, all that’s missing are bayonets on the AKs. Outside Debaltsevo, the men were booted out of their vehicles in a field, and given the order to seize a fortification or a blockpost. And forward, just like meat. When they started up on us with 120 mm [guns], with RPGs on the vehicles, people… they just vomited. Direct hit from an RPG – only hands and feet remain. No one is sent out to battle from Molino without training, but they only manage to learn the basics of how to shoot so as not to die immediately.”

Such tactics continued in Syria:

“What are we doing there? We go as the first wave. We direct the aircraft and artillery, push back the enemy. After us merrily go the Syrian special forces, and then Vesti-24 [a Russian state TV station] together with other Russian state television crews with cameras at the ready to interview them.”

ChVK Wagner fighters receive 240,000 rubles a month (around US $3,500). Fontanka asked why volunteers were signing up for a fifty-fifty chance of being wounded or killed for such a salary.

One returning fighter replied:

“Have you been traveling outside your Petersburg recently? Beyond Moscow and Petersburg there’s no work anywhere. If one is lucky – 15-20 thousand a month isn’t considered bad, but the price of food – it is as if we live in Antarctica. There’s a queue in Molino.”