In Russia This Week, you will find links to the stories of Russia Update in the last week and to special features, plus an article following up on the news and trending topics below.

Last issues:

– What Happened to the Slow-Moving Coup?

– All the Strange Things Going On in Moscow

– Remembering Boris Nemtsov, Insider and Outsider (1959-2015)

Please help The Interpreter to continue providing this valuable information service by making a donation towards our costsâ€.

Nothing seems as ubiquitous now in Russia, southeastern Ukraine and Russian-occupied Crimea as the St. George ribbon. The orange-and-black-striped ribbon was once used by Imperial Russia on medals for military campaigns; exploited without reference to St. George in the Soviet era; revived by President Vladimir Putin in 2005 to counter the 2004 “Orange Revolution”; and more recently it found its way into the Russian-backed insurgency in the Donbass last year.

It was not always so pervasive and its use now by the Russian government, Russian ultranationalists and Russian separatists in Ukraine is a tale of manipulation of symbols and meanings largely to counter other symbols — in this case, mainly those of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the “white ribbon” anti-Putin demonstrations in Russia.

With the 70th anniversary of Victory Day this year, the St. George ribbons — already a frequent sight — began to appear everywhere — from car antennas to t-shirts to flip-flops and car dealership ads.

In a piece titled “Victory of Idiots,” Novaya Gazeta covered some of the most ridiculous uses of the ribbon:

On advertising (for sanitation pump services):

Get a discount on a Hyundai:

On flip-flops:

It’s hard to remember now, when the Kremlin and its propaganda arms like RT.com and Channel 1 have made it seem as if there was “always” a St. George ribbon for May Day, that it was not used with anywhere near this level of visibility until this past year.

People who lived through the Soviet era don’t recall the ribbon as something “everybody” wore on their lapels or tied to their cars. And that’s because in the Soviet era, a ribbon with those colors only appeared within a specific context: on military medals and the stylized rendering of those medals on posters, postcards and stamps.

The St. George Cross was used in Imperial Russia and then reinstated by President Yeltsin in 1992.

The colors of orange and black symbolized fire and gunpowder, say some sources. This is based on the writings of Count Giulio Litta in 1833 explains one source:

The immortal law-giver, in founding this medal, supposed that the ribbon unites the colors of gunpowder and the light of fire.

But the same source also explains another version for the origin; in the opinion of Serge Andolenko, a general of the French Army and a famous falerist or collector of medals, the colors were taken from the state emblem (a black eagle on a gold background).

Wikipedia shows the the Imperial Order of St. George with orange-and-black stripes going back to 1807:

Cross of St. George (1807-1917)

The St. George medals were abolished by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Revolution and substituted with the Order of Glory which used the same orange-and-black striped ribbons:

President Boris Yeltsin reinstated the St. George cross as the highest military order in 1992 after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Russian Federation’s first medals deliberately used orange and black stripes.

All four classes of the St. George Cross in modern Russia.

UPDATE:

As some are careful to point out, the Guard’s ribbon thus isn’t the same as the St. George ribbon, which was taken from the Russian imperial standard’s colors of yellow and black:

Yet variations in the colors do appear — the St. George Cross of World War I vintage looks to have an orange-and-black-striped ribbon:

The variations has ensured endless arguments on Internet forums. Blogger Oleg Kashin wrote on his Facebook page last year (translation by The Interpreter):

Obviously we’re all great falerists, but there is a mistake everyone is making: in 1913, there was a new statute for a medal of St. George – and there the stripes on the ribbon were no longer yellow but orange. That is the black-orange ribbon is not [from] Stalin but Nikolai II.

If the statute from Nikolai II is authentic — it’s a description in writing of the color orange, not just a photo or object that might have faded — that would seem to clinch the issue — the orange-and-black stripes were used by in the later tsarist period, not just gold-and-black stripes; there also appears to be evidence of its use in the 1700s.

Thus, the use of the same colors throughout Russian history (the last tsar’s use) enables the Kremlin today to say there is continuity going back before World War II, and then to claim the appearance of the same colored ribbon during and after World War II as part of the same heritage.

In fact, if we look at a movie reel of the first Victory Day parade in 1945, we don’t see any St. George ribbons as decorations or bunting or posters

anywhere, but only the ribbons on some soldiers’ chest medals.

Some critics of the propagandistic use of the ribbon say it wasn’t used at all in the Soviet Union.

Postcards from the era show the ribbon was in fact used, however in posters and postcards showing medals or as the edging on stars — commonly on the “Glory” medal.

Here’s one from 1969:

From the 1970s:

From 1975:

From 1984:

While it’s possible there were some lapel buttons or ribbons in the Soviet era, we couldn’t find any examples or anyone who recalled them.

In 2003, we can see one sign on Red Square with the ribbon attached to a medal.

Photo by Ivan Secretarev/AP

It was not until 2005 that the Russian government decided to detach the ribbon from the military medals and make it something that “everybody” could wear. There are two different versions of the story of how this came about.

According to one story told by the Russian independent media and Ukrainian media, the Kremlin’s “grey cardinal,” Vladislav Surkov, came up with the idea as a way of providing a patriotic alternative to the “Orange Revolution” and its orange ribbons in Ukraine. Fearful that the democratic movement might spread and undermine state power, Russian propagandists worked overtime to discredit and distract from the Ukrainian demonstrations and prevent them at home.

Red Square during the Victory Day parade in 2008. Photo by Getty Images.

Red Square during the Victory Day parade in 2008. Photo by Getty Images.

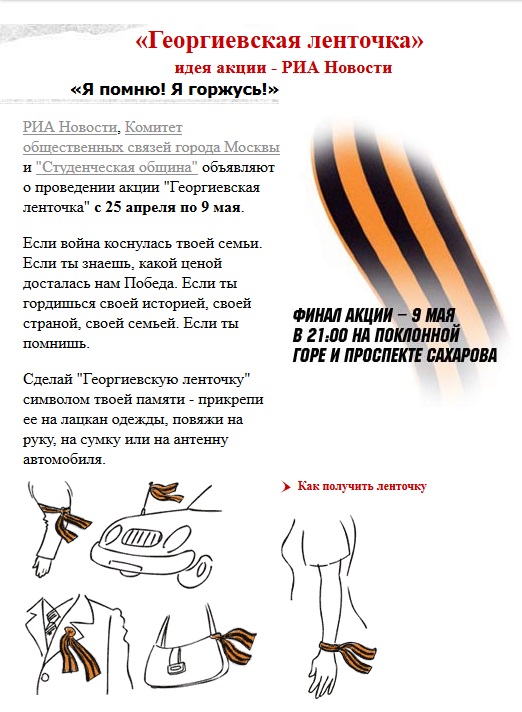

According to another version of the story told by state journalists in 2007, RIA Novosti’s Natalya Loseva, who was responsible for public programs, came up with the idea to promote involvement in May Day with a special website (Sputnik International replaced RIA Novosti’s English-language site in a reorganization of state media last year):

The campaign started shortly before May 9, 2005, during the preparations for the 60th anniversary of victory in World War II. RIA Novosti launched an online project (http://www.9may.ru/) to collect the reminiscences of people whose grand- and great-grandparents fought in the war. Striped ribbons, 50 centimetres long and 3.5 centimetres wide, were distributed free in the streets all over Russia as souvenirs to accompany it.

The ribbon idea was a brainchild of Natalya Loseva, RIA Novosti Internet Projects Director. The Student Community public organisation, the Moscow municipal administration and many others promptly joined in.

It may have been that Surkov promoted his idea through RIA Novosti.

Yuliya Latynina also reported in 2014 in an article for Novaya Gazeta (excerpt translated by The Interpreter) that Loseva had conceived of the idea. She uses the term “Nashisty” which was a play on the word “Nashi” (Ours), the name of the youth movement, and “fascist,” to convey their aggressiveness. The word “gopota” comes from the term gopnik or thug.

Then the Nashisty and other pro-Kremlin youth began to happily hand them out on the streets. To be honest, at that time, handing out the “St. George ribbons” seemed to me to be merely the apotheosis of a kind of “triumphant gopota” of historical amnesia and total mockery over the very military valor which they pledged to protect.

The problem is that the St. George ribbon is not a banner, not a flag, not a button and not the word “Spartak” on a t-shirt. It is a sign of military valor. It is the ribbon of the St. George medal instituted by Catherine the great in 1769, and she awarded it not to dogs or cats or automobiles as a hood ornament.

[As she said:] “Not by high nobility nor the suffering of wounds by the enemy are those given the right to be graced with this medal; but it is given to those who not only fulfilled their post in everything under oath, honor and duty but were distinguished above this by some special courageous act.”

[Russian war heroes] Suvorov, Potemkin, Rumyantsev, Barclay de Tolly, and Kutuzov who merited this medal of valor by their labors and wounds could imagine that it would be handed out by immature boys and girls in passageways at random and that carelessly tied to an automobile, they would fall in the mud under the wheels of other cars.

While journalists wrote about it, we couldn’t find pictures of its actual use in those years.

From the May 8, 2005 page of 9may.ru at Archive.org we could find a diagram instructing Nashi followers in fact to tie the ribbon to antennas, arms, and purses:

In 2006, Kommersant wrote (translation by The Interpreter):

One of the most all-national PR campaigns, run in

Russia last week, illustrated how fears of the “Orange Revolution” in

Russia are still alive and the battle against it continues. The

ubiquitous St. George ribbon was supposed to erase from national memory

its older competitor — the orange ribbon.

From a look at the Nashi demonstrations of 2007, we can see that the ribbon is in fact not visible; they more often used their own red and white flag which seemed to imitate the St. Andrew (Andreyevsky) Russian naval jack.

According to a Bloomberg report, Loseva herself is not happy with the monster her creation has turned into, as she said on her Facebook page recently:

“No comment. No, I am not coming. No, I’ve had nothing to do with

this for several years. Yes, it could have been predicted. No, I always

believe in intellect and taste. Yes, time will tell. No, I’m not sorry.

Yes, the manure will dry and fall off. Sooner or later.”

In any event, the purpose seemed to be both promotion of patriotism tied to war heroism and a revival of the Soviet cult of the Great Patriotic War (as World War II is called in Russia), and a counter-action to the “color revolutions” in Ukraine and later other countries.

Some have pointed out that wearing military medals if you did not actually receive one is an administrative offense under Russian law. But clearly any such consideration was long ago thrown by the wayside.

Russian specialists Sean Roberts and Robert Orttung explained the ongoing controversies around the St. George Ribbon in a piece this week for the Washington Post:

In the run-up to the May 9 holiday this year, Moscow is promoting its connections between World War II and the war in eastern Ukraine through an unlikely strategy – by trying to monopolize the lapels of post-Soviet citizens. This situation has its origins in an ingenious, participatory, and continually evolving Russian nationalist propaganda campaign originally created by Putin’s administration in 2005 as part of the 60th anniversary of Victory Day – the wearing of the Ribbon of St. George or the Georgievskaya Lenta.

Since 2005, the Georgievskaya Lenta, an orange-and-black-striped ribbon associated with an 18th century czarist Russian military medal, has become an increasingly important part of celebrating the end of World War II in Russia, and it has also been exported by Russia to other post-Soviet states as an overtly Russian symbol of these states’ shared history in the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany.

Russia’s neighbors were not too happy with this promotion; Kyrgyzstan, for example, changed the color of their May 9 ribbons to their country’s flag.

As Jamestown Foundation noted earlier, in the Caucasus and Central Asia, the St. George ribbon is associated with the St. George cross medal which was awarded to invading armies that conquered them, as an Uzbek blogger explained.

Here’s a medal “for campaigns in Central Asia 1853-1895”:

In 2012, hardline Vice Premier Dmitry Rogozin, who is responsible for defense and space, promoted the use explicitly as a counter to liberal anti-Putin demonstrations:

Promoters or vendors with armfuls of St. George ribbons began

appearing in the streets of Simferopol in February 2014 during pro-Russian

demonstrations.

Here’s one on February 27, 2014, captured by Arthur Schwartz of EPA:

When they first appeared in the spring of last year outside the context of Victory Day worn by Russian-backed militants, journalists didn’t recognize what they were. Among the first times when the ribbons really began to stand out as a “statement” was when Robert Serry, an envoy sent by the Swiss chair-in-office of the OSCE, was detained by the militants.

As we wrote at the time on Day 16 of the Ukraine Crisis in a blog titled “Russian Provocations”:

A number of reporters have noticed people

in civilian clothing in Crimea wearing orange-and-black ribbons at

demonstrations, at army and air bases, and at the storming of government

buildings. This is the St. George ribbon,

historically used in memory of World War II, but in recent years

adopted by Russian nationalists in Russia at their marches and rallies.

Now it has been imported to Ukraine. The New York Times writes

that the men who detained UN Secretary General’s special envoy Robert

Serry, former Dutch ambassador to Ukraine, were wearing the St. George

ribbons:

Serry was detained by armed people at the building of the

Ukrainian Naval Staff Headquarters. They blocked the envoy’s car. He

was forced to seek refuge in a coffee shop.

According to James Mates, head of the European bureau of ITV News who

was in the group of journalists who accompanied Serry, when he tried to

leave the coffee shop and get into the car, people who had gathered

nearby began to show “Russia! Russia!” and “Putin! Putin!” According to

Mates, many of them were wearing the St. George ribbons.

On March 7, the St. George banners appeared at a pro-Russian march in Kharkiv.

On March 20, among the “little green men” — Russian troops without insignia — assaulting the Ukrainian ship the Kmelnitsky was one wearing a St. George ribbon:

Around this time was when the term koloradtsy or “Colorado Beetles” began to be used to describe the pro-Russian demonstrators and fighters, due to the similarity of the orange-and-black stripes of the insect.

This isn’t the first use of the term but it’s an early one.

Translation: Near the Kramatorsk City Interior Ministry [police station], a crowd of patriots have gathered. Russian saboteurs have left the Interior Ministry. Several local Colorados are standing around.

Interior Minister Arsen Avakov used the term on his Facebook page on April 13, 2014 (The Interpreter has translated an excerpt):

1. The ATO [Anti-Terrorist Operation] has begun in Slavyansk. The Anti-Terrorism Center of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) is leading it. All forces from all force divisions of the country have been brought in. God speed!

2. (Unofficial, emotional)

Who are these idiots that send people to Kharkiv, which barely returned to peaceful life with gigantic efforts — without fights and bonfires? Who are the puppet-mansters who do this at a moment when we have to concentrate ourselves on the Donbass?! Who are you, you bad guys and provocateurs?! You want to light Kharkiv again with Molotov cocktails and arouse the dregs of the Colorados, and frighten the neutrals with the “militant rightists”?! You want not only Donetsk and Lugansk burning by nightfall but Kharkov?

Putin, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and other leaders wore St. George ribbons on May 9th at the Red Square parade in 2014, which thematically tied “the little green men” seen in the Crimea and the Donbass to the Russian leadership.

Photo by TASS

Now that the long-anticipated 70th anniversary of Victory Day has come and gone, will the ribbons go away? If anything, they are likely to be promoted even more in the run up to the 75th anniversary and will now be as hard as Colorado beetles to eradicate because they have become implanted in the national consciousness.

Some people like this young man who composed an ode on the subject have tried to call to Russians’ conscience and urge them to treat the ribbon with more respect and only use it for the medals of valor and not as clothing accessories. But they are not likely to be heeded.

And the ribbons are likely to continue to serve as a divisive symbol in

Russia as can be seen in this confrontation between a nationalist

journalist wearing the ribbon who was refused entry to the front of the

procession in memory of slain opposition leader Boris Nemtsov. The

journalist kept claiming that the ribbon was a symbol of victory in

WWII and respect to his grandfather, but the Nemtsov supporter said that

Berlin was taken by the Soviet army with red flags, not black-and-white

ribbons, and that the ribbon had become a symbol of killing in Ukraine.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick