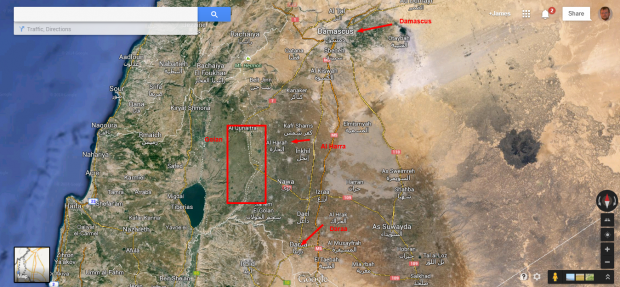

The Syrian rebels, in what appears to be a joint operation between several Free Syrian Army (FSA) brigades, have captured an important Syrian Army installation overlooking to town of Al Harra (or Tal Harra), in Daraa province (map). The capture of the base would be significant news in and of itself. The base towers above Al Harra, a town situated between Daraa — an area where moderate rebels have been more prominent than in northern Syria— and Damascus, the embattled capital where the Assad regime has been on the advance. The base is also very close to the Golan Heights, the nearby border of which is marked by the red box in the map below.

This area is a key focus in the battle for control of southwestern Syria. In the last month the regime has made significant advances just north of here, outside of Damascus, but has lost more control in Daraa province. Between the end of September and the start of October, the Assad regime’s attempts to recapture Deir al-Adas, less than 10 miles to the northeast of Al Harra, were rebuffed by rebels. During the incident, the regime reportedly used chlorine gas to weaken the rebels, but ultimately even those efforts were unsuccessful and the Syrian Army pulled its forces further north. Assad’s typical targets for this level of aggression, the use of chemical weapons, are massively strategic areas around Damascus and Aleppo, so the fact that chlorine was reportedly used as part of the assault on Deir al-Adas demonstrates the importance of this region. The road between Daraa and Damascus is one of the only roads that connects the capital to the south. If the regime loses control of this towns along the road they will lose control of southern Syria. But even more worrying for the regime, that will create a direct route between Jordan, where the U.S. has been arming and training moderate rebels off and on for years, and Damascus.

#Syria #Daraa Walk in captured army base on Tel Harra https://t.co/IUtMBVFrQ1 — Mark (@markito0171) October 6, 2014

The Assad regime is losing ground in this territory. In this map below, Al Harra is approximately in the center:

(Before/After) Map, shows the Rebellion advances in this area in the last 5 months, from May to October. #Syria pic.twitter.com/Y9zbGGdgkB — archicivilians (@archicivilians) October 6, 2014

But the fall of this base is making headlines for a different reason. Syrian rebels who overran the base have found evidence that the Syrian Army was not alone on the top of the hill. The rebels say that their evidence proves that Russian military intelligence officers were also operating on the base, and appear to have left some of the equipment — and pictures — behind. A video tour of the facility, posted on Youtube (below, though here’s a copy) shows that inside the base there is evidence of the presence of Russian “Spetsnaz,” special forces units who were members of the radio electronic intelligence agency of Russia’s GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate, the Russian military’s chief foreign intelligence unit).

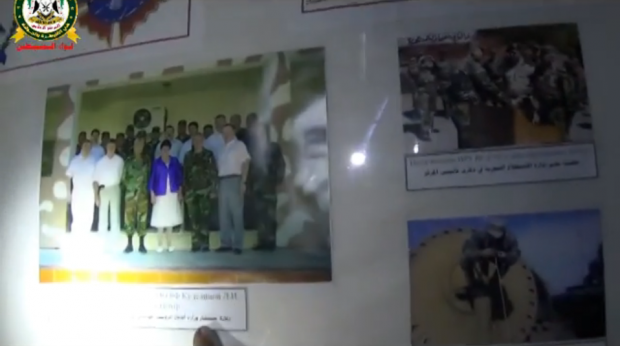

The video shows a wall adorned with pictures, many of them labeled in both Russian and Arabic, which appear to show a Russian GRU SIGINT (Signals Intelligence) unit operating on the base. The Oryx Blog has posted and analyzed a dozen screenshots from the video, and besides a minor translation issue (which we’ll point out below) the post explains the significance of the pictures.

On the 5th of October 2014, the Free Syrian Army captured the Центр С or المركز س ‘Center C or Center S’ SIGINT (Signals Intelligence) facility (logo on top) jointly operated by the Russian Osnaz GRU radio electronic intelligence agency (logo on the right) and one of the Syrian Intelligence Agencies (logo on the left). Situated near Al Hara, the facility was of vital importance for the Assad regime as it was responsible for recording and decrypting radio communications from every rebel group operating inside Syria, making it likely the Russian-gathered information at this facility was at least partially responsible for the series of killings of rebel leaders by airstrikes.

Translation from [the three minute and 8 second mark of the video – The Interpreter]; ”A directive issued by the surveillance office on May 31 to eavesdrop and record all radio communications of the terrorist groups, directive signed by brigadier-general Nazir Fuddah, commander of the first center.”

The base appears to have been called “Center S,” not “Center C,” where the “S” could possibly stand for “Syria.” “Osnaz ” is a term that is sometimes used to describe small “Spetsnaz” teams, Russian military special forces units which typically operate in secret. The logos in question are in this screenshot below:

According to one of the pictures on the wall, the base may have been visited by a very-high ranking member of the Russian military:

Various photos on the wall inside the captured facility once again emphasise the Russian involvement in the Middle East, showing even a map of Israeli Armed Forces bases and units. Other photos detail Russian personnel working at and running the center, as well as highlight a visit by Kudelina L.K., Counselor to the Minister of Defence of Russian Federation.

Lyubov Kudelina, Deputy Minister of Defence for Financial-Economic Work, is a female, which matches the screenshot from the video below.

Obviously, the screen-capture from the video is not high quality so no definitive identification can be made, but the woman in blue does strongly resemble official pictures of Lyubov Kondratyevna Kudelina:

According to Oryx, the man speaking in the video says another picture is labeled “‘Рабочий визит начальника ГУ МВС ВС РФ” – Visit by the chief of the Main Directorate of International Military Cooperation of the Armed Forces of Russian Federation.” While the name of this person is never mentioned in the caption of the picture on the wall, Sergey Koshelev is the chief of the Main Directorate of International Military Cooperation. Koshelev appears to be a grey-headed older man, and the man in the photo appears to have black hair, but since the picture is low quality and doesn’t show the Russian official from the front, it’s hard to analyze.

The other pictures appear to show Russian soldiers working at the base with Syrian intelligence officers. There are several references to the collection of radio intelligence, and videos of the exterior of the base show large antennas and electronic receivers which could be used to monitor communications:

Russian Coordination with IRGC and Assad

If Russian intelligence operatives are running operations anywhere on Syria’s front lines, the area between Daraa and Damascus might be exactly where we would expect to find them, since this is an area where Assad’s allies have helped him defend in the past.

By the end of 2012 large parts of the Syrian Army had defected to the rebels who had established strongholds across northern Syria and had taken control of large parts of Syria’s second largest city, Aleppo. The regime had gone many months without even a hint of a victory on the battlefield. It became clear to many that there were very few things keeping the Assad regime afloat: air power supplied and maintained by Russia, tanks supplied by Russia, high ground defended by military bases and Russian-made artillery, and oil and money supplied by Moscow and Tehran.

To counter this, (as Michael Weiss, The Interpreter’s editor-in-chief, and I worked together to uncover), in the last few months of 2012 the United States began an effort to train and arm moderate Syrian rebels in Daraa province. Within months those insurgents, armed with Croatian anti-tank weapons, were winning battles and capturing large amounts of territory between the Jordanian border and the Syria’s capital city. The Obama administration had two modest objectives. First, force Assad to the negotiating table by weakening his firepower and technological advantages — and drain support from his key allies Russia and Iran. Second, because U.S. ally Jordan was absorbing an unsustainable amount of Syrian refugees, while also fending off attempts by radical Islamists in the Hashemite kingdom to migrate into Syria to join the rebellion, allowing the moderate rebels breathing space in Daraa would create a de facto buffer zone between Syria and Jordan.

However, as the rebels began to make significant gains around Damascus they began to complain about a lack of arms and ammunition. Clearly Washington, afraid that the rebels might actually sack Damascus or become too powerful to want to negotiate, cut the supply of weapons. What followed was months of stalemate around the capital.

The strategy did result, however, in changing Assad’s “calculus,” but not in the way the Obama administration had intended. By early 2013, with the regime losing ground, Iran significantly increased its military intervention in Syria, and the focus was the area around Damascus. In his highly regarded profile of IRGC-Quds Force Commander Qassem Suleimani, who had taken personal control of Assad’s anti-insurgency operations, the New Yorker’s Dexter Filkins noted:

Late last year [2012], Western officials began to notice a sharp increase in Iranian supply flights into the Damascus airport. Instead of a handful a week, planes were coming every day, carrying weapons and ammunition—“tons of it,” the Middle Eastern security official told me—along with officers from the Quds Force. According to American officials, the officers coördinated attacks, trained militias, and set up an elaborate system to monitor rebel communications. They also forced the various branches of Assad’s security services—designed to spy on one another—to work together. The Middle Eastern security official said that the number of Quds Force operatives, along with the Iraqi Shiite militiamen they brought with them, reached into the thousands. “They’re spread out across the entire country,” he told me.

A turning point came in April, after rebels captured the Syrian town of Qusayr, near the Lebanese border. To retake the town, Suleimani called on Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader, to send in more than two thousand fighters. It wasn’t a difficult sell. Qusayr sits at the entrance to the Bekaa Valley, the main conduit for missiles and other matériel to Hezbollah; if it was closed, Hezbollah would find it difficult to survive. Suleimani and Nasrallah are old friends, having coöperated for years in Lebanon and in the many places around the world where Hezbollah operatives have performed terrorist missions at the Iranians’ behest. According to Will Fulton, an Iran expert at the American Enterprise Institute, Hezbollah fighters encircled Qusayr, cutting off the roads, then moved in. Dozens of them were killed, as were at least eight Iranian officers. On June 5th, the town fell. “The whole operation was orchestrated by Suleimani,” [John Maguire, a former C.I.A. officer], who is still active in the region, said. “It was a great victory for him.”

The next towns to fall to the joint Hezbollah-Assad fighters were key suburbs of Damascus, freeing up Assad’s soldiers to take their fight further south, reversing many of the gains and sapping the momentum of the FSA coalition in Daraa. Once Damascus and Daraa were more secure, Hezbollah and Assad began to focus on Homs, to the north of the capital. The once ineffective Syrian Army, which had been on its back foot, had regained the upper hand thanks to command and control from Iran and foreign fighters from Lebanon.

Rebels Slated To Fight ISIS Attacked By Assad Near Russian SIGNIT Base

A key part of the Obama administration’s new strategy to combat the terrorist group ISIS is to train and supply moderate Syrian rebels who are willing to fight Islamic radicals like the Islamic State. But this wave of training is just the largest in a series of similar efforts, particularly noteworthy being the efforts in late 2012 and 2013 mentioned above. While there is debate about where these rebels will be trained — Saudi Arabia is a probable destination — the CIA already has a well-known training camp north of Amman, Jordan, and extensive contacts among FSA fighters in the south. While efforts to arm and train rebels may utilize similar connections in Turkey, it stands to reason that U.S. support for the southern rebels will also increase. As such, the base at Al Harra may have been on the front lines of Assad’s efforts to monitor and combat these U.S.-backed rebel groups.

Russian Spetsnaz and Mercenaries Are Already in Syria

It should not be a surprise that Russian troops are operating in Syria. As early as March 2012 sources in the United Nations Security Council were reporting that Russian “anti-terror” squads were arriving in the country, entering via the Russian military base in Tartus on the northwestern shore. At the time Russia denied the report, but Russia’s Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov did admit that his country had “military and technical advisors” in Syria. By May of 2013 there were whispers of a secret unit, Zaslon (or “Screen”), launching an operation in Syria. As Mark Galeotti, a specialist at New York University on Russia’s security services, observed in May 2013:

“Zaslon is perhaps the most secret of Russia’s many spetsgruppy or special forces detachments. It is part of the SVR, the Foreign Intelligence Service — specifically its Directorate S, responsible for undercover operations. Formed in 1998, Zaslon is tasked with covert missions abroad ranging from protecting officials in dangerous environments to conducting assassinations. It numbers some 280 operators, who are trained and equipped to the highest standards.

“Unlike most Russian special forces, Zaslon does not publicize its activities or even its existence. They have sometimes supplemented embassy security details in especially dangerous conditions; indeed, they provided security for former SVR director Mikhail Fradkov when he visited Damascus last year. They are typically used for more direct operations, though. Zaslon was rumored to be part of the operation to assassinate insurgents who kidnapped and killed four Russian diplomats in Iraq in 2006, for example, and they may be ready to free captured Russian military advisers.

However, according to one Russian report, two Zaslon elements were also deployed to Baghdad in the dying days of the Hussein regime. Their mission was to seize or destroy documents which Moscow would have found embarrassing had they ended up in U.S. hands. Given the scale and depth of Russian support for Assad, it could similarly be that they are also in Syria to cover Moscow’s tracks or else ensure that sensitive military technology — including new surface-to-air systems — does not end up in foreign hands.”

In January, 2013, a Russian judge, Sergey Aleksandrovich Berezhnoy, was shot in the face by Syrian rebels while purportedly “on vacation” in Syria, albeit a working vacation since he was escorting a team from the pro-Assad Abkhazian Network News Agency (ANNA) as it reported on regime-on-rebel fighting near Damascus. A manager for ANNA described Berehnoy as having “fought for five years as an intelligence officer in Abkhazia and in other hot spots of our vast Motherland,” a claim later taken up by Russian state television and then denied by Berezhov himself.

Then there is the ‘Slavonic Corps,’ a group of Russian mercenaries, recruited in St. Petersburg, who were hired to defend Assad’s oil resources east of Homs. Those men, most of whom were former Russian special forces soldiers, were almost surely fighting in Syria with the full knowledge and consent of the Kremlin.

The key difference, however, is that while the Slavonic Corps was fighting in a limited capacity to secure oil fields, and while Zaslon was allegedly hunting rebel leaders, the GRU units in Al Harra appear to have been working with the Assad regime to intercept communications and better execute Assad’s counterinsurgency strategy.

Spying on Israel

According to the Oryx Blog, which cites Debka File, a website connected to Israeli military intelligence, Center S was recently upgraded in “reaction to Iranian concern of the facility being too much focused on the Syrian Civil War, neglecting espionage on Israel.” No doubt the IRGC wanted ears closer to Jerusalem to warn of any impending aerial assault on Iran’s nuclear weapons program, but there is likely another impetus behind spying on the Jewish state.

In recent months, the Israel Defense Forces, fearful of how the ensuing Syria crisis unleash jihadists into the occupied Golan Heights, have also increased contacts with Syrian rebels in the southern regions of Quneitra and Daraa, while waging sporadic war against the regime. On September 23, the day U.S. and coalition warplanes began bombing the Islamic State in Syria, Israel shot down a Syrian fighter jet that had accidentally slipped into Israeli airspace while trying to interdict rebel advances to the Syrian-Golan border. As Ehud Yaari of the Washington Institute for Near East Peace writes, the rebels now control:

“…most of the territory adjacent to the 1974 Israeli-Syrian Truce Line, including the narrow demilitarized “Area of Separation” overseen for the past forty years by the UN Disengagement Observer Force. UNDOF was originally established by the Security Council to supervise Israel and Syria’s adherence to agreed limitations on their border deployments, but as a result of rebel advances it has now practically ceased to function except in a small remote sector on the slopes of Mt. Hermon. Its forces have abandoned bases and a string of other positions in Syria and discontinued inspections there. Meanwhile, UNDOF’s fundamental purpose on that side of the border — monitoring the Syrian army’s order of battle — has become largely moot because the Assad regime’s frontline 61st and 90th Brigades have completely collapsed.”

Previously, Syrian Army positions have been destroyed with Israeli Tammuk missiles in retaliation for shelling into the Golan, as IDF video footage has demonstrated. The map on the captured Spetsnaz SIGNINT facility, which is less than 7 miles from the Golan, shows “Israeli Armed Forces bases and units,” no doubt because Russian intelligence is trying to minimize the regime’s risk in losing more personnel and materiel to errant provocations, to which the Israelis unfailingly respond. Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s official affiliate in Syria, has been more circumspect in its dealings with its neighbor: thus far, no terrorist attacks have been waged by the group in the Golan or against Israeli forces.

But is there another reason for this SIGNINT facility’s base in the south?

As Yaari notes, Israel has treated around 1,400 wounded Syrians in Israeli hospitals for months and has dispatched humanitarian aid to villagers. But the IDF has also been coordinating with rebel groups, and though this relationship has yet to qualify as client-proxy in orientation, it remains that case that “a modest amount of weapons have been provided to [the rebels by the Israelis], mainly rocket-propelled grenade launchers.”

Should southern Syria proliferate with Islamic State militants, and should the undeclared “truce” between the IDF and Jabhat al-Nusra evaporate, then Israel may be inclined to invest more heavily in the moderate rebels, a policy which would affect the Assad regime as much as it would the radicals. And while it’s true that Moscow and Jerusalem have never been closer diplomatically, the Kremlin cannot afford to allow Israel to contribute to the further weakening of its most valued ally in the Middle East. Moscow Center knows and respects Israeli military and intelligence capability. It has everything to fear from Israeli intervention in Syria.