Maria (Masha) Alyokhina, a member of the punk rock group Pussy Riot, has written a letter from prison, describing the harsh conditions there. Alyokhina is due to be released soon, so the letter can be seen as more a witness for those prisoners who are still incarcerated. However, after publishing the letter in The New Times on December 2, Alyokhina then wrote a second letter on December 5th saying that all prisoners in contact with her have been punished because of the letter.

We have published both letters below. The top letter is the newest. It was published on December 5th and was translated by Pierre Vaux. — Ed.

IK-2 management is exerting pressure on prisoners following Maria Alyokhina’s piece for The New Times.

The editor of The New Times has received a statement from Maria Alyokhina, stating that following the publication of her article on the conditions in the No2 Nizhny Novgorod penal colony, the institution has begun to exert pressure on everyone who has been in contact with her.

The Statement:

Following my recently published article in the news magazine [further below], The New Times, about life in the Nizhny Novgorod colony for women (IK-2), pressure has begun to be exerted upon anyone within the colony who has had the slightest degree of contact with me. It seems that the operation is running around the clock, they are summoning dozens of people, even at night.

I ask all those, who have served time in IK-2, and feel that their rights have been violated, in terms of wages, working times, refusal of medical assistance etc. to come forward and talk about it.

I’m appealing to the women who have been freed – now nothing threatens you, but bearing witness from here means enduring hell until the end of one’s sentence.

I’m appealing to human rights activists, for help in gathering testimony from the free.

Right now, it is possible to change something in IK-2 for once. It hurts me to see how, under total secrecy and enforced silence, irredeemable things are going on. Don’t let them get away with it.

Masha Alyokhina

December 5, 2013

The following is Masha Alyokhina’s first letter describing the conditions inside her prison. It was posted on December 2, 2013, and was translated by Catherine A. Fitzpatrick — Ed.

On 21 October, The New Times published the research of Zoya Svetova, “Made in the FSIN [Federal Corrections Service].” This is a text about whom Russian prisoners work for. Maria Alyokhina, serving a sentence in Corrective Labor Colony No. 2 in Nizhegorodsky Region, read this article because she subscribes to The New Times.

After reading it, she sent her own text to describe what she has seen with her own eyes.

Special to The New Times

Corrective Labor Colony No. 2 is considered one of the best. It is within the city boundaries, on the left is the park and on the right is the Avtozavodsky Court of Nizhny Novgorod, a residential quarter, and newly- constructed apartment buildings.

They say that in the mornings and evenings you can hear a howl coming from the Corrective Labor Colony (CLC). That isn’t an animal. It’s we prisoners, lined up for inspection, “five at a time,” greeting the administration. The person responsible for the line-up commands loudly, “Attention!” and the rest respond in a loud chorus, “Greetings!” This is how politeness is taught. “Be polite to each other and in addressing the CLC personnel” – No. 8 of the internal regulations.

The inspection alone lasts a minimum of half an hour. The women stand outside for it in any weather unless it is pouring rain. For most of the year this means shifting from foot to foot from the cold and wind. The government-issue winter boots are made of material reminiscent of a single-layer oil cloth. In order to warm the soles, the prisoners use sanitary napkins from the free hygiene kits. No on knows the reason (but everyone curses it) as to why the administration does not allow counting by units.

They don’t like the word “barracks” here, but the dormitories cannot be called “home.” People say, “I’ll go back to my unit.” Prisoners in Russian colonies live in units. CLC No. 2 is, of course, no exception. The main building of the unit is the section where iron two-story bunk beds stand in several long rows. The “legal” space for women is reduced to three square meters – that’s approximately the width of the bed plus the space to pass between the next one. “In general, privacy was left at home,” is a reply you can hear from the wardens. “Here, everything is public.” The toilets, for example, are public. They consist of several rows of a stone elevation with a number of holes with a space no more than 20 centimeters between them. Women spend years having to meet their needs by crouching on their heels, bumping each others’ legs and waiting their turn for the toilet – a picture that is not very reminiscent of the “subtlety and refinement” about which you can read on the web site of the Nizhegorodsky Main Administration of the Federal Corrective Labor Service.

How a Person Turns into a Slave

“Every person sentenced to deprivation of freedom is obliged to work in places and at jobs determined by the administration of the corrective institutions” – this excerpt from Art. 103 of the Corrective Labor Code is known and invoked with satisfaction by the officials of the system. You need only two documents in order to turn a person into a slave: his own statement which begins with the words, “I ask to be accepted…” and the order from the head of the zone [prison camp] to be assigned to a job. There is no question of writing statements voluntarily; they will give you a timely reminder that “Every prisoner is obliged to work…” No labor contract has to be concluded, and there is no requirement to read and sign off on how many hours are supposed to be work and how much the prisoner will get paid . From the quarantine [after arrival], a women is assigned to a unit and within several days is already “posted to the industrial zone” (i.e. she is assigned to one of the brigades that work on shifts—The New Times).

Women are “posted” to work by lists which are called “orders.” They are written up every day. They are also brought back from work by lists; this is called a shift. The shift or post is an ordinary procedure, everyone goes through it who works in the plant. CLC No. 2 has a video camera that records the process: the long line of women shivering in identical green coats enter open iron gates beyond which is located what is officially called the center for labor adaptation (CLA). On the gates is the sign of the indu-zone [industrial zone]; while in line, women now and then say “I wish that indu-zone would burn down!” and meanwhile crows fly noisily around the roofs of the plants. And that’s how it is, six days a week.

Sewing Shop No. 2 is a virtually unventilated space with an exhaust pipe that leads to a pile of manure situated 5-7 meters from it. During the summer, women experience difficulty in the process of sewing due to the abundance of flies, the smell, and the rats darting between their legs. The floor is caving in, the plaster is falling out, and several of the machines lack safety guards, and on most, there is a weak grounding of the electrical wires. There is a lack of running water; there is one faucet for 100 people, water doesn’t flow from it, and it has to be brought in buckets from the administrative building. The maximum which can be received for working under such conditions, by fulfilling 140% of the norm, is 1500-2000 rubles. Shop No. 2 will never be seen by a single commission (usually they demonstrate the model shops No. 1 and No. 25); the wages for the seamstresses there amount to 100-200 rubles.

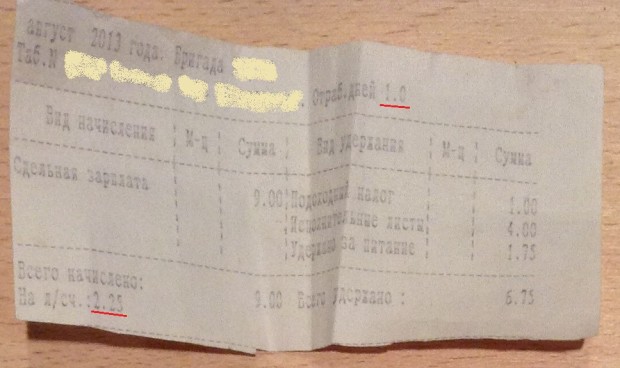

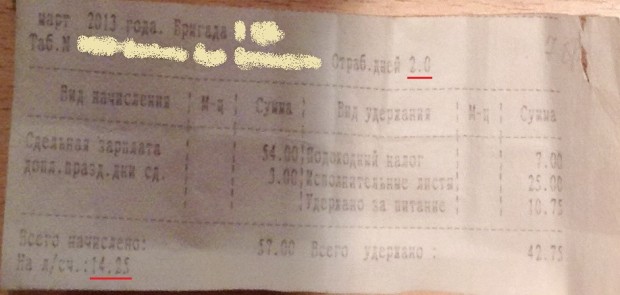

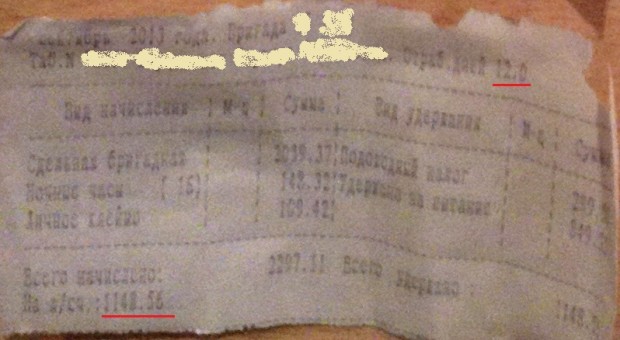

The confirmation of the wages and the length of service of the convict is the pay slip. These slips are handed out to every worker in person. At first everyone was extremely surprised that they worked for 6 days a week, but on the pay slips there are recorded only 5 or 6 days per month of work. Inquiries were made to the administration. But here, if you ask a lot of questions, your answer will be a report and a punishment. That means being subjected to humiliations at disciplinary commissions, after which you sit in the punishment isolation cell – a stone solitary box without warm things, tea or cigarettes, and few people want that, which is why questions disappear.

The work record is made up of the days worked. Women who have worked for 3 or 4 years receive a notice upon release that they have a record of only a year or less. Frequently there are cases when the annual paid vacation required by law has not been given for several years, and the convicts are told, “Work, or you will remain in debt to the colony” – the [daily] orders are destroyed, but according to the sheets, they worked no more than 10 days a month.

What is work, for example, in the cutting shop? Those who work there can easily be recognized from their blue boots. If you look at them more closely, you will see the same color on their hands and nails. This is bluing (a process of coating steel with anti-rust material) which is blown around the shop, mixed with dust and grease, because the ventilation works in the opposite direction. When I heard about this, I got the impression that the organizers of the work have brains working in the opposite direction; after all, work in this shop is dangerous. At the band knife machines or the cutters which women stand up at all day long (chairs are “not stipulated”), the sharp tin strips often break, and if they touch a person, the outcome can be lethal. The strips tear because the safety devices don’t work. It would be strange if they did work on equipment where the year of manufacture was 1979. And women are put on these machines without any training, put there at night, put there without sufficient lighting, with the dust and bluing flying around, which gets into your skin. Labor under such conditions is valued at 1000 rubles a month with all overtimes (and twice as less without them).

If you don’t work overtime, the attitude toward you can change. They punish you by not assigning you additional sleep (two hours on Sundays). Or by not giving you boiled water to drink during breaks. Or by refusing to give you a token – women are allowed to go to the toilet with tokens; leaving the shop without a token is considered a violation. Therefore some women take care of their needs in a bucket in an empty space next door.

Do the companies that conclude agreements with the colony know about these details?

For an order of 500 winterized suits for the company Slavyanka in Vladimir (TekstilProf, Ltd.) a brigade of 50 people is paid 35,000 rubles. Half of this money is kept back by the colony (for food), so it comes out to 300 rubles a month per person, and if there is a fine, which a convict must pay herself, then it will be less. In order to fulfill this order on time, the prisoners worked 14 hours a day at the end of November.

For orders from the Trud Plant CJSC, for whom CLC No. 2 makes plumbers’ clamps, you can be paid 30-35 rubles a month. For the same money, the prisoners can perform services in wrapping presents for the company Mir podarochnoy upakovki [Present-Wrapping World], Ltd. There are pay slips with pay of 2.5 rubles.

Most likely, on paper, the prisoners don’t produce anything at all, but for years only “provide services” and that’s why it costs so little. Labor inspectors could care less, and from here — from the zone – it seems as if labor inspections don’t exist at all anyway.

The Collective as a Means of Rule

A system in which a person has long grown used to be subservient, in which he has not only learned to be ideally subservient, but knows at which moments his subordination is advantageous to use, such a system can be maintained only by one thing: the collective. The collective means of influence is applied throughout the colony everywhere. In the industrial zone, there is the brigade, where one convict is placed to boss the others as brigade leader, and her duties, confirmed by the head of the colony, include reporting about all violations. In the units, there are persons put on duty who are “obliged to report,” and at the level of the colony such people are called “firemen” – those who formally are supposed to keep watch over the status of the fire-extinguisher but who in fact are watching over the status of people.

I am extremely baffled by the rule under which a convict is put on the job of “night duty” and her work consists of sitting up through the night in the kitchen and watching to make sure the others don’t walk around the unit. How does this work foster correction? It turns out that there are funds in the zone to pay for such “work,” but there aren’t enough to buy equipment, and that’s why loaders (women!) are hauling bales of paper weighing 400 (!) kilograms [880+ pounds].

The cafeteria workers whom I see every day, whose shift apparently lasts 16 hours, carry enormous (80-100 kg) barrels of cabbage every day. These same barrels are unloaded from trucks by hand by women from all the units, and this unloading doesn’t even count as part of their house-keeping work hours. “You’re doing it for yourself,” comments the colony management.

But who will treat the prisoners after such work? The appeals to the infirmary by one woman were ignored for half a year, and as a result she was taken away to the hospital and had a hysterectomy. They also found she suffered from hepatitis acquired in the zone. Another woman who suffered interruption of her HIV therapy now has cirrhosis. With a jaundiced face and eyes and open bleeding, she was brought to work in the industrial zone, and only put in the infirmary after the arrival of the Public Observation Commission and a therapist from the outside.

There are masses of cases related to failure to provide medical assistance. That is exactly why everything is done so that the institution remains closed to the maximum extent. Women know that if they begin to write complaints, their mental health will be threatened due to pressure. They say that before a large convoy was brought from Udmurtia to CLC No. 2, they were afraid to write even appeals of their sentence.

“If you die today, tomorrow I will receive an incentive for that”.

Recently, the governor of the region visited our colony. On the day before, a film about the mother and children’s ward in CLC No. 2 was shot. Everyone understood that the imprisoned mother, who stubbornly kept repeating for the camera that “we have a sanatorium here,” was lying, and whoever wasn’t able to lie was intimidated or locked up. Ironically, the facility where the problem convicts are locked up during visits from commissions is called the Cultural Education Unit. And in this same place, where “inconvenient” people are locked up under pretext of summons to the administration, during the evenings you can observe a line of quite different prisoners – these are women who have firmly embarked on the path of correction, those who learned, recalled and began to respect “the norms, rules and traditions of human community” (see Art. 9 of the RF Criminal Corrections Code). Their attitude towards other prisoners is briefly summarized by the principle about which Solzhenitsyn wrote: “If you die today, I’ll die tomorrow.” Or to be more precise, “If you die today, I’ll get an incentive for that tomorrow, and the day after, I will get early release” – that’s how approximately it sounds now. And in fact that’s how it works.

And although it is rare that anyone is released early from CLC No. 2, and no one is called to the early-release commission on schedule, the line to the offices is long. After all, in their baseness, people don’t thirst for freedom, but only watch as other people drown. To see whether they will ask for help or silently endure it. This is what is encouraged here, this is what, apparently, is the most reliable “tradition of human community.” Simple respect for those who maintain the system is beyond reach.

Thanks to them – they who have the word “law” written on their clothing – these lines of people are standing with reports and denunciations; the female zeks [prisoners] stand and rub their hands “Now I will sic these two sections at each other” or “now someone will go to the punishment cell.”

The incentive in prisoners of their capacity for betrayal, the squeezing out of them of the last that is human – this is preparation of the soil for recidivism. But under the conditions where the prisoner is a cost-effective property, and the purpose, written in the law, is to “correct the convicts and warn against the commission of new crimes,” has long ago been exchanged with the purpose of profit, the recidivist turns out to be profitable for everyone – the police, the courts, the prisons, the zones.

How much prisoners earn in their zone: pay slips