Readers might get the idea that the number of terrorist attacks in Russia is increasing because of a series of well-publicized suicide bombings in the central Russian city of Volgograd in December and earlier in the fall. With the Sochi Olympics coming up in February, a view of the map of terrorist bombings in the Russian Caucasus yields a sense that there are many such attacks, and they are growing closer to the site of the Games (although Volgograd is 420 miles away from Sochi).

The reality is that terrorist attacks in the past year leading up to the Olympics have statistically been lower than in past years, as not only Russian authorities claim, but as Andrei Soldatov, an independent researcher of Russia’s intelligence agencies, points out in an interview with Lenta.ru (translated by The Interpreter), and as the respected non-governmental monitoring group Caucasian Knot reports.

There are several factors peculiar to Russia to keep in mind in assessing this information to try to determine whether “less” means “more” for the future.

First, Russian officialdom has pulled off a linguistic legal trick that considerably politicizes the information and makes for the impression that Putin is “winning the war on terrorism” – a politicization that inevitably leeches into the relatively independent blogosphere as well. Under Putin, as Soldatov explains, bomb blasts in which only a few people are killed and which have no obvious “message,” i.e. a manifesto or letter to authorities, and which do not “seek to place pressure on government bodies” are not considered or investigated as acts of terrorism. With constant repetition, Mikhail Bakunin’s anarchist notion of the “propaganda of the deed” is now merely the “propaganda of the dead” – and often only warrants a murder or weapons investigation unrelated to terrorism per se.

Thus, if we are to believe Russian analysts, the Boston bombing, in which two American immigrants of Chechen and Dagestani descent, often described as “home-grown jihadists,” set off bombs that killed “only” three people while maiming dozens of others, might not have been called a “terrorist act” under Russian law because the pair had not produced any kind of demands or messages to the authorities before or during the attack, which was in a public square, and not directed at a government building.

Regardless, as Caucasian Knot points out, only 6 of the 32 blasts in the last year in the North-Caucasian Federal District and the Southern Federal District were booked as “terrorist acts” because multiple people were killed or – more importantly for the purposes of answering the question of whether there was “pressure on the authorities,” took place next to police stations or army bases.

Soldatov and others point to an intriguing reason for the lessening of bombs in the North Caucasus in the period leading up to the Olympics when “pressure on the authorities” might have been expected; they cite the February 2012 statement by Doku Umarov, head of the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, who announced that while there were street protests against the Russian authorities going on, he and his network of terrorist cells would refrain from attacking civilian targets, in the belief that the Russian people themselves had now at long last started resisting the hated Russian government.

They also cite a shift from large fighting units to smaller clandestine groups. The new cell structure of terrorist movements means some analysts begin to see them as unattached to larger, organized jihadist movements – as if rigid ideological control was dropped with physical personnel control — and there is a constant debate over that degree of attachment, as there is around the world, e.g. over the attack on September 11, 2012 in Benghazi. That Umarov could effectively enforce his five-month moratorium on terror over such a loose network of cells lets us know, in the North Caucasus anyway, that the ties aren’t so loose.

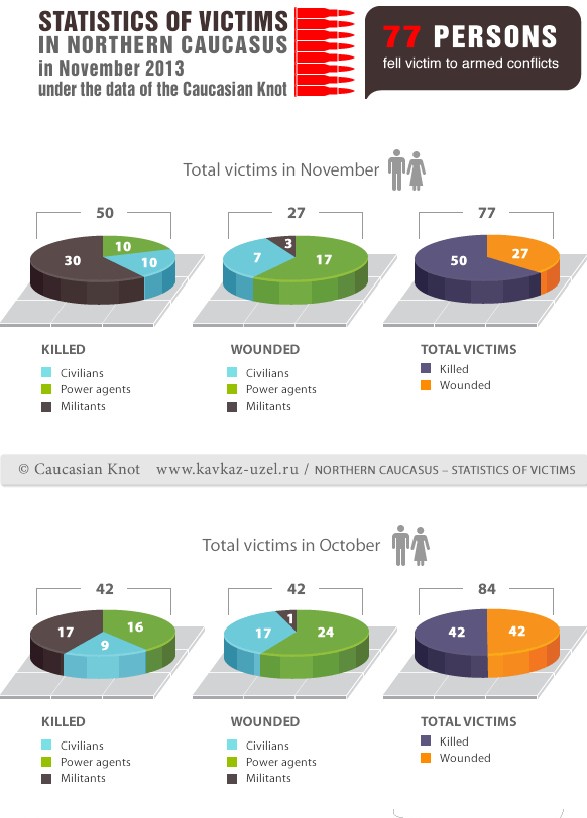

If we take a look at the infographs carefully prepared by Caucasian Knot (including the one below), we see an extraordinary number of incidents every month that never get noticed by the world media and even the Russian media; in November alone, 30 militants, 10 siloviki and 10 civilians were killed and that was nearly a lull.

Cars, stores, homes, and marketplaces are constantly blasted, then Russian Interior Ministry and FSB troops surround the homes of suspected militants and flush them out or bomb the houses if the relatives refuse to turn them over. Thousands of people have been beaten, jailed, or killed over the years in these operations. So many people have been arrested and tortured – and so many policemen killed in retaliation – that the police from Dagestan themselves recently made a sojourn to Moscow to deliver an impassioned plea for “the center” to “do something”; 1,290 people were brought in and 1,121 people were released without a police report of their detention made in the last year alone, they said. In 2012 alone, 110 policemen were killed in anti-insurgent operations and 205 were wounded. Things were so bad that even these police, themselves often charged with torture tactics, complained about the too-high level of torture which wasn’t working: “On ten pages here we have written what tortures are being suffered by those detained in the police stations. The soul shudders. These are the people who are making up the Interior Ministry of Dagestan,” said a police chief.

Yes, Russian counter-terrorism (which is really counter-intelligence is run by a counter-intelligence expert now) is overkill, as these many awful incidents indicate. Putin’s idea of pre-Olympics anti-terror sweeping is to arrest…an environmentalist, and to question and rattle dozens of other peaceful activists in civil society such as Circassian nationalists. As Soldatov and others have pointed out, Russia has always either poorly understood – or deliberately conflated — the difference between counter-intelligence and counter-terrorism and has created a high level of distrust both within the Russian intelligence community (if one could use that term) about each other’s departments and rival agencies and in the population at large (hence the phenomenon of “truthers” in the Russian independent media and blogosphere who believe that the Russian government is behind these attacks and who are sometimes the recipients of leaks from dueling agencies trying to discredit each other).

Even so, the Islamist backlash to brutal counter-insurgency tactics is authentic and growing — and now the xenophobia of ethnic Russians is growing proportionately. Umarov’s moratorium on terrorist attacks while he was waiting for anti-Putin demonstrations to work their magic seems odd; surely he realizes these new protest movements mainly centered in Moscow and St. Petersburg by and large have no sympathies for even the human rights concerns of the Northern Caucasus; as we saw with the nationalist marches and pogroms this fall, some have a decided anti-Caucasian cast.

As we know, a hallmark of the movement coalesced around Alexander Navalny has been cries to “stop feeding the Caucasus” in the belief that federal funding only fuels organized crime and corruption. Yet as we have seen with such chilling reports as the fate of Lt. Gen. Sergei Bobrov who tried to clean up police abuses in Dagestan and was then mysteriously recalled by Putin, a lot of the “organized crime” is the cover-ups of numerous abductions and killings of people whose offenses often only seem to amount to complaining about rough police tactics against themselves and their relatives.

Thus, while Putin may be technically “winning the war on terrorism” through media control, linguistic legal maneuvers and of course brutal police tactics (that might or might not include faked terrorist attacks or “assets gone rogue”), the result has only been to fuel resentment and set up the next round of real terrorist attacks committed by real committed extremists who are now even more unpredictable. After the blasts, 4,000 policemen were dispatched to Volgograd in an “Anti-Terrorism Whirlwind” as the Russian authorities dubbed it. Soldatov believes the series of bombings in Volgograd are a distraction technique anyway, designed to siphon off counter-terrorism resources – if so, the terrorist technique worked like a charm.

Does that mean that something ghastly could be in the works for the Sochi Olympics? The world trusted the London Olympics because British police methodically went about capturing the perpetrators of the 2005 metro bombings and reassuring the public, not randomly arresting Muslims. Putin is far less persuasive, especially when he rounds up suspects that one day are female and the next day turn out to be male perpetrators. We are thus kept off balance – which is a state that both Putin and the terrorists are happy to keep us in.