Last week we reported how volunteer Russian fighters from the Ural Mountains region went to fight in the Donbass alongside the Russian-backed militants in the Prizrak Brigade there, but came back somewhat underwhelmed by the living conditions and lack of combat opportunity. These were the people sent by the Sverdlovsk Fund for Spetsnaz Veterans and given a ceremonial send-off by Cossacks in the Urals town of Yekaterinbug. These volunteers seemed to spend most of their time guarding checkpoints, some of them got sick with pneumonia and ear infections and went back home after a month.

Paul Goble has a summary of an article published by reporter Dmitry Volchek of Radio Svoboda (the Ukrainian service of the US-funded Radio Liberty) titled “Life Among the Thugs.” He interviews a Russian businessman named Bondo Dorovskikh who came back from the war even less impressed than the Urals volunteers, saying he was enrolled “not in an army but a gang.”

In both these stories, the fighters were sent to the Prizrak (Ghost) Brigade run by Aleksei Mozgovoy, a native of Svatove District in Lugansk Region who has been reluctant to join the other forces in the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Lugansk People’s Republic.” According to the pro-Russian blogger Colonel Cassad, despite Mozgovoy’s resistance to subordination to the other leaders, on April 2 his unit was said to be incorporated into the 4th Territorial Defense Battalion of the “Lugansk People’s Republic” (LNR). It’s not clear how that’s going.

In a context where very few of these stories of returning soldiers have been leaked — the volunteers and their families can suffer reprisals — it’s interesting that we now have several. This could be merely due to the fact that the gap between the propaganda on state TV and the reality of the war has grown so shocking that fighters become determined to speak out — as Dorovsikh explains to Svoboda.

Or it may be in this case that some forces within the LNR want to discredit Mozgovoy by showing he treats his fighters poorly and that they are even involved in theft and abuses against local people. Such offenses the LNR has ruthlessly suppressed in its own dungeons or by extrajudicial execution, as occurred last year with the battalion leader Aleksandr Bednov, known as “Batman.” It might also be possible that Moscow is looking for ways to wind down the involvement of such volunteers, and may want to let it be known that conditions are poor and the local population hostile to incoming Russians – although that seems unlikely, as the Russian-backed fighters continue to bear down on Shirokino and other pressure points along the front line without ceasing.

Bondo Dorovskikh is not a name that has come up before in the “Novorossiya” cause. An old forum from 2006, NGE.ru, which describes itself as “an independent trading platform for petroleum products from Russia and the CIS,” contains some posts with customer feedback about the Nitrokhim company in St. Petersburg. The name “Bondo Dorovskikh” is listed among those associated with this company who have not paid back debts. It’s a distinctive name and likely the same person, as in the interview (see below), he mentions that he had a ban on travel abroad due to a debt. The same name appears at biznesrazvedka.rf which means “Business Intelligence,” showing him as general director of the Neftealyans oil company in Ivanovo. Another site shows him involved with three more oil companies in Ivanovo Region.

Among the interesting features of Dorovskikh’s account is that he say that Russian state television influenced him to go and fight Ukrainians. He read that Eduard Limonov’s Other Russia party was recruiting fighters, then eventually made his way to the DNR’s recruiting office operating without hindrance in Moscow – but then was sent to fight with the LNR. When he got to Alchevsk, he saw Russian officers in the Prizrak Brigade, but local people told him they didn’t want to join Russia.

The Interpreter has translated an excerpt of the interview. The questions from Volchek are marked in bold.

So you went exclusively out of ideological considerations without material incentive?

There could not be any question of the material, because I bought all the ammunition myself, and a bullet-proof vest. It cost me about 100,000 rubles to deploy there and to outfit myself. There it was not a question of money; now they pay $360, and not everyone gets that. Some people go there for adventures, some for combat experience… Everyone has his reasons. Of course, most of these people there are unsettled somehow. It’s like ISIS — why do people go there? They think they will be needed, they think they will be in demand. It’s the same thing. When you land here, literally in the first few minutes you realize that this is not a military division, this is a real gang.

Do you recall what was the last straw that made you finally decide to go? Was it some broadcast on television or did you read something on the Internet?

I had the channel Rossiya 24 going in my head constantly, where they showed the latest news from Ukraine. And then I even said to myself: I won’t go there, I don’t need that. Every morning I would say that to myself. But as soon as I turned on the television, where from morning till night they only talked about that… Of course the mass media influenced me.

Had you been in Ukraine before, do you know this country?

No, I had never been there, this was my first visit.

Where did you turn in order to become a volunteer?

There are several opportunities on the Internet. There is the international brigade from [Eduard] Limonov’s party Other Russia; you send a short form to an e-mail address, they tell you were to go, let’s say, to Shakhty, and then from Shakhty, they dispatch you to the area of the militia. I wrote to everyone, I wrote to the international brigade. In Moscow the DNR has opened up a recruiting office. I wrote there, I was given contacts, they apparently approved my application. They approve everybody’s application. Then they give you a telephone number. When you arrive in Rostov-on-Don, you call that number, they tell you where to go, where the staging area is.

So there are no inspections, no one takes an interest in your military experience, or checks whether you are a provocateur or not?

No, there aren’t any inspections at all. Moreover, there were cases when somebody crossed the border with a Xerox copy, they didn’t have any ID at all. When we came to the militia, they just asked our last name, name and patronymic. A photograph of you is taken, and you are given an ID based on the last name you provided.

Do they give you weapons?

Very quickly, they give you a weapon immediately. In fact, I was a sniper, I had an assault rifle, and I had a rifle. I had a grenade-thrower and a machine gun, in principle I had all the small arms. When we arrived at the position in Nikishino, at the front line, local militia were there, each one had a clip of ammunition and an assault rifle, but they weren’t dressed appropriately. But we had everything, we were outfitted completely — with grenades, machine guns, RPGs, the ammunition for them, absolutely everything. We even had our own vehicles to get around in.

Was this all given to you in Rostov Region in the training camp?

No, nothing was given out in Rostov Region, it was all given out on the territory of the Donbass. In Rostov Region, the militia who previously were tank gunners in the army were sent to the training ground, they were trained at that training ground, and formed into crews. There they were given weapons. I saw this myself. These tanks were driven on flatbed trucks to the border of Russia and Ukraine, where they crossed on their own and headed directly to the combat zone. But I was given a weapon in the Donbass.

How did you cross the border?

We were driven through a field. The first time we came officially to a checkpoint, but I had a restriction on going abroad, I was not let through. Then the border guard said to me: there are no problems, the guys will escort you. And they really did escort us, they formed a larger group, about 15 people, and that day we simply drove across the field, there isn’t a border as such there.

Did you have a restriction on travel abroad due to a debt?

I had a small debt with the court bailiffs, therefore I was barred from travelling abroad, I didn’t know that.

[…]

When I was in Prizrak, the brigade practically controlled the city of Alchevsk completely. Our combat units were at the line of contact in Vergulyovka, in Komissarovka and in a few other towns. About 100-150 people are in Vergulyovka; in Komissarovka there are small units, and all the rest are in Alchevsk. In principle, the DNR and LNR did not recognize the Prizrak Brigade. They had an internal confrontation, and they put restrictions on the delivery of arms. There was a time when was not much armaments coming here from Russia — no artillery or tanks — but in Prizrak, they somehow contrived to solve these problems. There were several dormitories: volunteers constantly came from Russia and also other countries. The only ones who trained were the Spanish; they had an international company — Spanish, Italians and French. All the rest had this system: the company got up in the morning, they had roll call, line-up, and then the same roll-call at night. All the rest of the time the militia walk around Alchevsk, picking up scrap metal, taking down iron gates here and there, looting, and then turning everything in [to a scrap dealer] so they have money to go drinking and to buy some smokes. They are left to their own devices. Here and there they get drunk and shoot at each other. There was even this incident: one of them got drunk and wanted to throw a grenade into the room but they grabbed him in time. Such a peaceful life. Whoever is bored is sent to the front line.

So they didn’t pay any compensation, they had to earn some money by picking up scrap metal?

Essentially, yes. Some of them sold their weapons. Russians collect money, rations, they send ammunition, bullet-proof vests — this was all sold and drunk up. That was life.

[…]

The local people who served with you in the brigade, were they ultra-patriots of the Donbass, or did they have mercantile interests or were they simply indifferent to politics?

I think they could care less about politics. For the most part these are people with criminal records, and in fact repeat offenders. I have photographs which hung in the barracks, I photographed them. The comical thing is that these former convicts are hunting for former police officers. No, they are all far from politics. In the DNR, they were paid money, they went there exclusively to sit out the war so they would get at least some pay. All the rest are just thugs who have been given weapons. Furthermore, the militiaman has power like no other. There are no laws there, and when they are driving vehicles the militia always run the red lights. If the local people see that armed people are driving, of course they let the militia threw because the militia are armed. The militia say, “They respect us, we can run the red light, they shouldn’t stop us.”

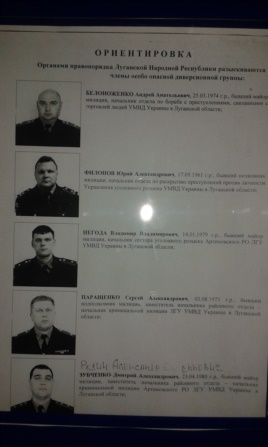

Wanted poster of former policemen who served under the Ukrainian government who were sought by the Russian-backed militants. Photo by RFE/RL

[…]

Did the Ukrainians observe the ceasefire and not return fire?

No, of course it happened that they fired heavily on us. But I saw what kind of losses there were, our guys made constant raids there. I saw two Ural trucks burnt, then a tank damaged, then a BTR damaged. They didn’t make raids on us from their side. Although I understand perfectly realistically, that we could have been easily beat from Kamenki, where a large number of the enemy were located…They just didn’t feel like it.

Were there a lot of people killed in your unit?

No, on our side in Nikishino, only one person died within a month, he was wounded in the head by shrapnel. On the other flank, where there was a company, there was a fighter named “Biker,” I didn’t hear from them that people were killed.

You said Prizrak had conflicting relations with the DNR. How was this conflict expressed and what were its reasons?

The DNR and LNR did not want to recognize Prizrak, it was a political question. They proposed to Mozgovoy that he go into the LNR not as a whole brigade, but be broken up in parts, so he wouldn’t have any power. Of course he didn’t go for that, he wanted to remain an independent figure.

Did you directly communicate with him?

I said hello to him, but I never talked with him. I did talk with Strelkov, but that was back in Moscow. I accidentally ran into Strelkov, and we talked about Mozgovoy. He said it was the only commander he still trusted.

[…]

We went into this territory, and Russian authorities are supporting terror. If we had not gone in there, if Russia had not helped the militia, there wouldn’t be thousands of people killed, there’d be nothing there. What did it start with? Strelkov came there with his group, Strelkov is a military man, given the opportunity, he will fight his whole life. I was such a fierce advocate of this movement, I agitated people to go there, but when I was coming back, the FSB agent at the border stopped me, and we had a long chat. I talked as openly with him as I’m doing now with you. Furthermore, he said: before you, 180 Russians went back last week. They just asked him: only you don’t tell anyone about this. I said, when I get back, I will talk on social media everywhere so that people do not go there because it is completely unlike what they are showing you. There are murders there, and robberies. Furthermore, from the very first moment I realized that if someone was going to kill me here, then most likely it wouldn’t be the armed forces of the Ukraine, not the enemy, but simply one of the militia who on a drunken spree would shoot you.

For additional translation see Lugansk News Today.