Staunton, August 26 – Russian government media outlets pushed demands for the federalization of Ukraine after the Kremlin indicated that was what Vladimir Putin wanted and then almost as quickly toned down its promotion of that idea apparently after it began to resonate in the regions of the Russian Federation itself.

At the request of Znak.com, the media research firm Medialogy counted the number of references to the idea of federalization of Ukraine in Russian government media, including First Channel, Russia 1, NTV, Vesti FM, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, Komsomolskaya Pravda, and Izvestiya.

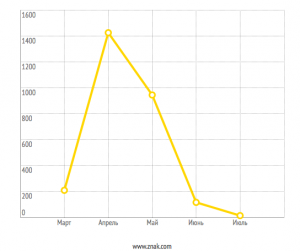

In March, these outlets referred to “federalization” 209 times; in April 1424 times; in May, 944 times; in June 116 times; and in July, only 14 times, a pattern that reflects the way in which the Kremlin media created an issue and then backed away from it as the regime’s priorities shifted and the risks involved in promoting that idea became apparent.

Medialogy experts explained this and related patterns of Russian government media coverage of Ukraine by suggesting that “for Russian propaganda, the task of creating the image of the enemy is primary relative to the task of promoting its own values and demands,” a pattern that sets Russian propaganda under Putin apart from that of other countries.

Aleksey Makarkin, the deputy head of the Moscow Center for Political Technologies, told Znak.com that he did not see anything “illogical” in the way the Russian government media had dealt with this issue.

It is the case, he said, that “initially” no one in eastern Ukraine took the idea seriously because it was obvious that the task ahead “was not in federalization but in the maximum rapprochement with Russia either according to the Transdniestria variant or what would have been ideal the Crimean one.”

According to Makarkin, “the demand for ‘federalization within Ukraine’ was addressed more to the West in order to show that there moderate politicians call for the broadening of the rights of their territories for reform and that the Ukrainian authorities were not listening to these demands.”

Openly separatist demands are one thing, he continued, while “federalization is a moderate demand.” But “the West did not accept this game having from the beginning adopted an absolutely pro-Ukrainian position.” After the events in Odessa on May 2, Makarkin said, Moscow stopped talking as much about it as well.

But Gleb Kuznetsov, a Moscow political consultant, disagreed. He told Znak.com that the inconsistency in Moscow’s treatment of federalization reflected the fact that “the Russian authorities cannot formulate a precise picture of the future from their own side.” And this is reflected in the fact that Russia is struggling not for something but against “enemies.”

As such, Russian propaganda is very different from its American counterpart, Kuznetsov said. The United States, he said, first specifies that “the American people want the following because its values are such and such and then the entire picture is pushed forward on the basis of these demands.”

Russian propaganda, in contrast, “does not specify what the Russian people need, what the Russian world is, or what its values and interests are. As a result, we turn out to be in the position of a victim: ‘they are beating us; we will grow strong in response.’” That message is not the best one to be delivering either at home or abroad, Kuznetsov suggests.