The previous post in our column Putin’s Middle East Pivot can be found here.

During the 2008 campaign season, the Democratic nominee for the next President of the United States, Barack Obama, expressed his frustration at the Middle East policies of the incumbent president, George W. Bush. The American people, Obama said, were tired of war. The US had toppled two governments in the Middle East and yet had failed to bring peace or security to the region. The US had overreached, had become arrogant. Its nation building adventures were failures.Obama argued that it was time to rethink America’s foreign policy.

After thousands of lives lost and trillions of dollars spent on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, few Americans disagreed with those assertions. For a multitude of reasons, Obama beat his opponent John McCain by ten million votes and 192 electoral college delegates. The mandate was decisive. It was time for a change.

After taking office, however, Obama made it clear that he did not intend to abandon the Middle East. Instead, he sought to build new partnerships there with civil society. The new president traveled to Egypt where he gave a now-famous speech at Cairo University. In what has come to be known as the Cairo Speech, Obama offered ” a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world, one based on mutual interest and mutual respect, and one based upon the truth that America and Islam are not exclusive and need not be in competition.” He described the tensions between the United States and “Muslims around the world” as having roots in “historical forces” fed by “colonialism… and a Cold War in which Muslim-majority countries were too often treated as proxies without regard to their own aspirations.”

Obama also laid out a few persistent problems that were plaguing the relationship between the US and the Middle East. From the Iraq War to the divisions over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, from the proliferation of terrorism to the threat of nuclear proliferation in Iran, which could spark an arms race. On that last point, Obama was adamant. The world would have to work together to keep nuclear weapons out of Iran’s hands, but “no single nation should pick and choose which nation holds nuclear weapons.”

If Obama defined his predecessor’s approach as heavy-handed unilateralism, Obama hoped to replace that dynamic with international and cross-cultural cooperation, rather than the imposition of America’s will on the region.

But what if that cooperation never materialized? What if the United States’ pullback in the region, its attempt to avoid imperialism, left a power vacuum that was filled by even less altruistic forces, ones which played an under-recognized role in messing up the region in the first place? What if the United States abandoned its leadership role in the Middle East in the name of avoiding colonial ambitions, only to see another colonial power fill that void?

Russian President Vladimir Putin was asking those same questions.

Obama “pivots” to Asia, Putin pivots to the Middle East

The Obama administration described its desire to focus more on economically building bridges with the developing economies in Asia than in militarily building nations with the struggling Middle East. But this disengagement would take time, and history was not going to stop while the Obama administration shifted direction. When huge crowds of protesters took to the streets of Iran in 2009 following the rigged presidential election, the administration had an easy choice. It interfered minimally, encouraged the protesters, and hoped for change.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recognized the potential in the 2009 Green Movement in Iran. The Green Movement was non-violent, secular but not irreligious, and was focused on supporting the democratic process, human rights, women’s rights, economic modernity, and international cooperation. It was not pro-Western — the Iranian people are far too proud and far too aware of Western interference in their history for that — but the movement was inherently rationally self-interested, which meant that diplomacy had a real chance of success should the movement succeed. Clinton also recognized that, by and large, any attempt to steer that process would backfire.

As someone who covered the events and had contacts in the State Department at the time, it was also clear to me that the State Department believed strongly that what started in Iran would not end in Iran. Long time US allies like the Mubarak government in Egypt and the Saudi royal family were advised to adopt a reform effort or face potential consequences. A year and a half after the Green Movement started, however, the “Arab Spring” emerged, posing a unique challenge for the United States. By the time Tunisian president Ben Ali fled his country, the effort to encourage gradual pro-democratic reform had run out of runway but had failed to launch.

When the Arab Spring began, Barack Obama, preferring to stay out of the Middle East rather than engage the US in an uncertain situation, by and large stayed quiet or backed America’s allies. Mubarak was encouraged by Obama to step down, for instance, at the last possible moment when it was already clear his government would collapse. Little was said, and less was done, to condemn the brutal crackdown against protesters in Bahrain, or the Saudi invasion which propped up the Bahraini king once it was clear that government had little local support. The US knew who these dictators were, and Obama, desiring to disengage and move on from the region, was hardly eager to champion the unknown and uncertain democratic process at the expense of longtime allies.

Colonel Gaddafi, the ruthless dictator in Libya, forced Obama’s hand when he immediately responded to protesting civilians with bombs are artillery barrages, and a horrified world looked on. The State Department was particularly vocal in their concerns. The pro-democracy movement which they had been rooting for since Iran’s uprising was finally taking hold. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and United States Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power, in particular, were fully aware that such a movement would be fragile. If the US allowed tyrants like Gaddafi to carpet bomb democracy, what would happen elsewhere in the region?

Gaddafi’s fatal flaw was not mass murder, it was impatience. He immediately resorted to the most extreme forms of violence, while the promise of the Arab Spring was still making headlines across the globe. By the time Syria’s unelected “president,” Bashar al-Assad, was using his air force to flatten his cities, the world — particularly the American people and the White House — had grown tired of the story.

But there were two key resources that Assad had and Gaddafi didn’t — a friend in Moscow, and the brains to use him.

Putin’s Middle Eastern summer

Some commentators take a look at Russia’s current intervention in the Middle East and claim that it was inevitable. Syria, they say, was a Russian client state. Russia is situated relatively close to the crossroads of the world, and so their interest in the region is a more natural fit than that of the West. Russia is also a petro-state, and so economically they have shared interests with the Middle East.

All of this is revisionist history.

In Libya, Russia had been a long-time on-again-off-again friend of Colonel Gaddafi. Yet, despite losing billions for dollars in arms contracts, Russia never lifted a finger to stop the UN and NATO from toppling Gaddafi. It was only after Gaddafi was toppled that Russia used the incident to criticise American policy. Now, the NATO action to remove Gaddafi is cited by Putin as an example of how American leadership just makes a mess of things. Interestingly, American isolationists make the same argument. Neither ever considers what Libya looked like before Gaddafi was removed, or how Libya is still in far better shape than Syria where Assad is still in power. Moscow’s role in the 2011 Libya intervention was to let the United States take ownership of a situation that was destined to be problematic, no matter what actions were taken by Washington.

Elsewhere in the region, the Russians never vocally championed unrest in pro-US countries. There’s no sign of them offering any significant levels of support to the opposition movements in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Kuwait, Egypt, Morocco, Bahrain, or anywhere else. Russia never used its influence at the UN, its significant state-operated media outlets, or its bully-pulpit to weigh in on this environment. In fact, if anything Russia was even more stand-offish toward the Arab Spring than the Obama administration. To Putin, pro-democracy uprisings of any sort, anywhere, were viewed as an existential threat.

What Vladimir Putin Learned From The Arab Spring

Five years ago the world was glued to Twitter, Internet news agencies, and live television, where one could watch the "old world order" fall apart in real time. On December 19, 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi's vegetable cart, his livelihood, was seized by Tunisian police.

If the US strategy in the Middle East failed, they failed because of the actions or inactions of Washington, not the policies of Moscow.

Nowhere is this distortion clearer than in Syria.

The US broadcasted its support for the pro-democracy protesters in Syria almost immediately. It called for Assad to step down. It pushed the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for action to stop Assad. By late 2012 it was actively arming rebel groups. All of these efforts were half-hearted, and several of them were paused or aborted at various stages, but for years there was no obvious commensurate Russian action.

Yes, Russia supported the Assad regime from day one. Putin used his veto power to stop the UNSC from approving any action. Yes, Russia also serviced Syrian aircraft and provided the Assad regime with weapons and ammunition. And, yes, Russia knew full well that the Assad regime was committing war crimes with these weapons. Russia could also have played a constructive role in convincing its ally to step down, reform, or at least keep the violence to a minimum. Again, because the anti-democratic kleptocracy of the Putin system viewed the pro-democracy movements anywhere as a threat, it chose to do the opposite. Russia is morally culpable for all of this.

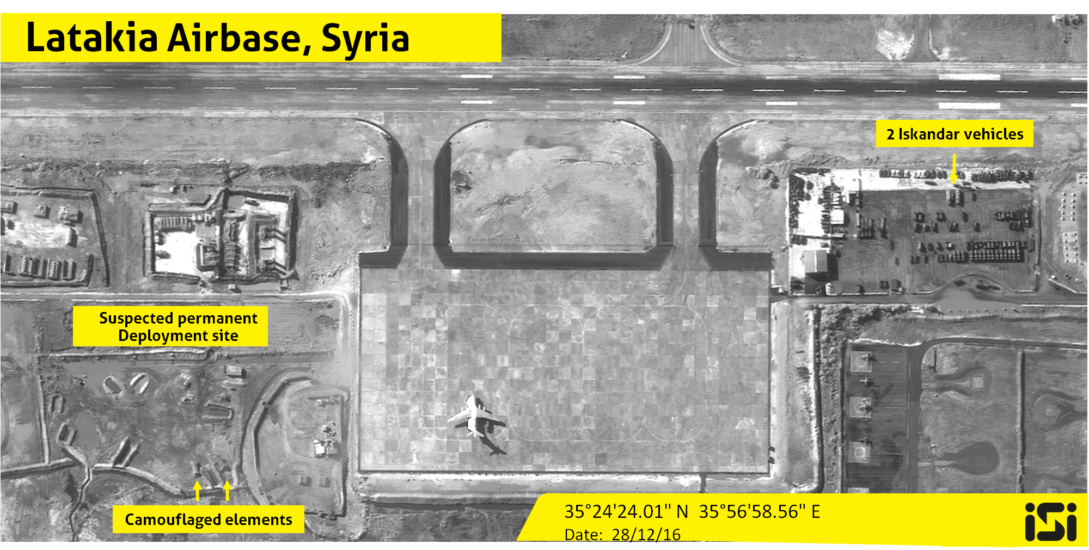

But at any point in time before September 2015, more than four and a half years after the start of the crisis, the world could have stopped Assad without running even a remote risk of triggering an armed conflict with Russia. Russia had all-but abandoned its bases in Syria in 2012. In fact, if one revisits the arguments made against military action against the Assad regime following the 2013 chemical weapons attack, nowhere did anyone argue that bombing Assad would risk war with Russia. This is a new narrative which has only emerged in the last 15 months.

American foreign policy is pulling back. America’s leadership role in the world has been lessened. The American people continue to vote for increasingly-isolationist leaders and policies. This was not an accident, it was by design. Russia has simply taken advantage of this dynamic. As the United States pivoted away from the Middle East, a revanchist Putin regime pivoted to the Middle East as a consequence.

The Middle East is losing local autonomy

If the hope was that an American pullback in its role in the Middle East would empower the people of the Middle East to govern themselves, the opposite has taken place. In Egypt, the people rose up against a military dictatorship. For a variety of reasons, their democratically elected government failed and was replaced by a military dictatorship. In Turkey, a NATO ally and formerly a symbol of democracy in the region has been disenfranchised by decades of American foreign policy and has moved toward autocratic Islamic rule. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has purged his opponents, has all but destroyed freedom of speech and the free press.

The World Is Less Safe Than It Has Been Since The End Of The Cold War

The crises in Ukraine and Syria have undermined the geopolitical balance that has kept us safe for generations It's perhaps an outdated cliche that voters do not care about foreign policy.

Putin Is Not Withdrawing From Syria, He's Just Getting Started

Russia appears to be gearing up for the next chapter of the Syria war, but the media is reporting that they're withdrawing

Iran’s hardliners have significant military and political influence in Iraq and Syria, and are arming rebel groups in Yemen. Hezbollah, a terrorist group, has expanded its military capabilities and has taken a leadership role in the Syrian conflict, bringing it closer than ever to it’s benefactors in Damascus and Tehran. Saudi Arabia is fighting a proxy war against Iran in Yemen. And Russia is now playing a vital role in the region despite having paid little attention to it in the post-Cold War era.

All of this, of course, ignores arguably the most dangerous threat, that this new rising axis of power in the Middle East — Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia — have been unable to check the rise in Sunni extremism. The extremist group Islamic State may have suffered military defeats, but it’s virulent ideology will continue to eat away at global security for years to come. Al-Qaeda and other hardline Islamist groups, on the other hand, have flourished, nearly unchecked in recent years.

Analysis: IS's Imminent Death Could Be Hiding Bad News

In 2014, the world was gripped by news of two deadly epidemics. Both were bloody, vicious afflictions that killed many who came in contact with them. Local populations were being devastated, but so, too, were foreigners who traveled to affected areas to help. Fears spread quickly that both would cross borders, infect cities, and threaten major events.

To blame any one of these developments on a specific policy or administration would be a vast oversimplification. The problems in the Middle East are complicated and go back much further than the Obama administration. The bottom line, however, is that US policy — both its overreach and its pullback — has not made the Middle East more secure. The opposite is true. It has left a vacuum that is now being filled by Russia and Iran.

Putin’s pivot to the Middle East is real, and this new reality will play a major role in shaping geopolitical balance and stability in years to come.