In Russia This Week, you will find links to the stories of Russia Update in the last week and to special features, plus an article following up on the news and trending topics below.

Top Stories:

–Volunteer Urals Fighters Return Home from ‘Lugansk People’s Republic’

–Residents of Chita Assemble to Protest Governor’s Inaction as Wildfire Area Doubles

–Wildfires Ravage the Transbaikal

–Mikhail Khodorkovsky Speaks at Stanford University on Future of Russia, Ukraine

– Russia Lifts Ban On S-300 Sale To Iran

– Google Renting Server Racks to Store Data in Russia – Sources

Last issues:

– What Happened to the Slow-Moving Coup?

– Can We Be Satisfied with the Theory That Kadyrov Killed Nemtsov?

– All the Strange Things Going On in Moscow

– Remembering Boris Nemtsov, Insider and Outsider (1959-2015)

Please help The Interpreter to continue providing this valuable information service by making a donation towards our costs.

After Putin’s marathon call-in on Pryamaya Liniya [Direct Line] yesterday, April 16, he held a press conference where presumably the questions were a bit more spontaneous but not out of bounds. Here, too, reporters set up softball pitches that gave Putin an opportunity to prevaricate, such as “how will the war in Ukraine end?” Some bolder reporters tried to catch Putin out in contradictions, such as asking why Russia couldn’t return the Kuril Islands to Japan if it took back Crimea and recognized it as “ours.”

But these mass media propaganda events, where the questions were arguably even sharper than in previous years given the war in Ukraine and Russia’s upheavals, illustrate a paradox in dealing with what has historically been called “the Big Lie” at the heart of Kremlin disinformation.

And that is, the harder and more “authentic” the questions – even with people sending videos from the mud and poverty of their collective farms — the more Putin’s evasive, duplicitous and misleading answers acquire a life of their own, as if the sharpness of the questions themselves provide a kind of authenticity to the answers. The reporters are usually not allowed to follow up, press conferences like this don’t occur very often, and in the state media, there will generally be no way to provide alternatives.

So the exercise leaves us with the same disinformation we’ve had for a year: there is no Russian military in Ukraine; the war is the Ukrainians’ fault; the West only exploited this misunderstanding to impose sanctions which were in their selfish economic interests anyway; and while Russia is poor, it is honest and the government is doing everything possible to help people.

The war is “above all the affair of the Ukrainian people…and they have to fulfill the Minsk accords,” said Putin. Yet it is Russia that launched the war, and Putin has never explained why, if the Crimean people’s free will was to join Russia, this had to be done with force and haste, with “little green men” and with suppression of the Crimean Tatar people, Ukrainians and other minorities and their media as well as many other critics and groups.

Russia has “no military presence” in Ukraine, yet as we have documented countless times on our Ukraine Live blog, there are Russian tanks and troops in the southeast of Ukraine. The response to Russians watching this claim and commenting on Twitter was to upload the photo of Dorzhi Batomunkuev, a severely burned tank gunner wounded outside of Debaltsevo, now recovering in his native Buryatia. There are many other such photos, and yet these facts, like argumentations about the instigation of the war or the rationale of using violence in the Crimea, don’t penetrate the plexiglass of Putin’s “other world” — as German Chancelor Angela Merkel once dubbed it.

Putin’s own logic on Crimea can’t apply to the Kuril Islands, as he explicates for the obstreperous reporter who tried to catch him in a contradiction. The reporter characterizes Putin’s position about Crimea as believing the Crimea was “primordial Russian territory” but even here, Putin says “it is not quite that” and explains (translation by The Interpreter):

No, our approach to relations with Japan on a peace treaty and on territorial issues has not changed at all in connection with Crimea. In that regard I would like to draw your attention to the fact that when we speak about Crimea, we speak not only about the primordial belonging of Crimea to Russia — we speak also of the people who live there, we speak of how democracy — and it would be a good thing for all our partners to remembers this — in both the East, whoever is not in agreement with this, and in the West, and in Europe and on the American continent — that democracy is the power of the people and power relying on the will of the people. So thus in Crimea this is not just territory — people live there who came to the referendum and voted for reunification with Russia. And their choice has to be respected.

As for the islands which you mentioned, people live there who would hardly vote for reunification with Japan. This is an absolutely different situation related to the results of the Second World War. Russia, by the way, if you go deep into the story there, also can regard these territories in different ways.

Japan pushed back after the press conference, saying it had not stopped talks. But the dispute remains over Russia’s insufficient offer to return only a small portion of the land, and only if the Japanese renounce claims to the rest of it, a position Tokyo does not support. There’s also Russia’s insistence on the 1956 Joint Declaration ratified by the Japanese parliament, which in fact did not settle the islands dispute. Japanese does not recognize that the disputed islands are part of the Kuril chain and say they are not covered by the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1971 which stated that Japan had to give up all claims to the Kuril Islands after the war.

Yet none of Japan’s interests or the understanding of the past international treaties shared by the West matter, because Putin’s notion of “democracy” trumps all — and is backed up by military force. Japan strongly protested Russia’s recent military drill on the islands.

The problem with this self-serving and instrumental notion is that it is inconsistent — democracy is blocked if it occurs in Chechnya or Karelia or Yakutia or anywhere where groups of Russian citizens have expressed a desire for freedom from the oppression of Moscow Center and have been denied it — sometimes violently under other doctrines that trump democracy, which is national security and the integrity of state borders. And if the democracy looks like it isn’t going Moscow’s way, then Russia could flood in ethnic Russians and Russian speakers loyal to Moscow who could then simply overrun local populations even if indigenous – a point which has been made historically with Ukraine. Alternatively, Russia can occupy territories and expel the inhabitants — as indeed it did with 17,000 Japanese, which is why “the will of the people” in Sakhalin doesn’t contain Japanese people today.

If Putin is convinced that the results of the Crimean referendum are legitimate — the international community rejected this notion by voting for a resolution to uphold Ukrainian territorial integrity in the UN General Assembly — then why did he send in GRU spetsnaz, as Putin later admitted, and use such force and haste while shutting down free media? The methods used alone tend to beg the question, even if a case could be made that a fair ballot might yield similar results.

Russian soldiers in Crimea in March 2014 carry VSS Vintorez silenced sniper rifles known to be given to GRU spetsnaz

In short, a notion of democracy, and popular will of the people in territories, basically come down to what the Kremlin wants them to be.

“After the annexation of the Crimea and war in Ukraine, many in the West began to perceive Russia as a threat to international security. Are they right? Should Russia be feared?” asked another reporter.

Indeed, the use of force, the suppression of the Crimean Tatars, Ukrainians and other minorities all justify not only international perceptions of Russia as a threat, but Western sanctions and reinforcement of NATO and other diplomatic measures to deter Russian aggression.

Yet Putin replies:

“No, they are wrong. I think this thesis is used in the interests of other states which want to create the image of an enemy in Russia and use that enemy image in order to preserve their leadership in the Western community.”

The notion of the “enemy image” as induced for selfish economic competition was prevalent in Soviet propaganda and persists today, with no more rationality than it had years ago. Why would the Western powers need to put Russia down to succeed, if they could do better by pursuing friendship and trade?

But like so many of Putin’s hortatory affirmations, the logic doesn’t matter because the psychological effect is to create the phenomenon of being the “alternative pole” in the “multipolar world” where capitalist “imperialists” are said to “dominate” to the world’s detriment with their nefarious “interests” and their false notions of democracy — as Putin implies by his remonstrances about the West somehow needing to accept that democracy applies to the East as well as the West.

Yet again, there is no logical explanation as to why these alternatives to the rich and powerful West have to be violent and damaging and aren’t built on their own demonstrable successes instead of invasion of other countries. Yet Putin says, incredibly:

“Russia is not conducting any expansionist policy.”

This, despite Russia’s essential annexation of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, its actual annexation of the Crimea, it’s defacto control over much of Donetsk and Lugansk regions and the “frozen conflict” of Transnistria. Kosovo’s independence, handled after demonstrable Serbian aggression and mass crimes against humanity tried in the Hague, within an international framework over many years and with the kind of recognition that the rump former-Georgian territories never got, hardly trumps Russia’s actual expansion.

Yet Putin repeated three times in this press conference that the Crimean Anschluss was not about “primordial” land but “the will of the people” and “power relying on the will of the people” and that “the people of Crimea came to the referendum and expressed their opinion and we believe that everyone should respect that opinion.”

The Western notion of democracy would include respect not only for minorities such as the Crimean Tatars but freedom of speech, assembly, and association — all violently suppressed since Russia occupied the Crimea. We have to conclude that Putin’s notion of “the will of the people” really only means some of the people, and the will of the people as long as it is expressed in alignment with the powers-that-be — as in the Soviet era the “advance guard of the workers” and the “leading role of the Party” overturned actual popular will.

Will the people watching Putin’s performance on state TV, with choreographed questions and sanitized presentations, see anything that will shatter this “other world” that Putin manufactures?

Certainly some viewers are going to identify with the homemade videos of people standing in the burnt ruins of their homes or attempting to drive along knee-deep muddy roads full of pot-holes or struggling to find places for their children in day care centers which reinforce their own negative experiences of reality so at odd with the promises of Putin’s “other world.” They will not be mollified by promises that someday it will get better.

A man stands in the burnt ruins of his home in Novokursk after wildfires swept through the town in April 2015. He appealed to the president for help in a video address to Pryamaya Liniya.

And some people came away with not reassurances but a slap in the face from Putin, such as those who had mortgages denominated in foreign currency who now can’t pay them with the fall in the ruble. Putin told them they just shouldn’t have ever gotten such foreign currency mortgages in the first place. That these were legal and encouraged and advantageous to oligarchs Putin supports doesn’t matter.

But ultimately, the message of Pryamaya Liniya is summed up in the Russian archetype of the Good Tsar and his supplicants, one reinforced in the Soviet era with paintings like Serov’s famous Lenin and the Petitioners –- come on sufferance, on our terms, and you might get a scrap. And Russian television viewers will have little option but to participate in this model.

A British ex-pat in the dairy business, John, was featured at length on the call-in show. He bent over backwards to express his loyalty and appreciation of Russia and his people – he was married to a Russian woman and had five children — but said he just couldn’t make ends meet. He hadn’t made a profit in 23 years, and was about to close his business down because of the impossibility of getting costs covered when higher prices couldn’t be charged for milk, and the expense and difficulty of loans. His adult children refused to take over the business under these terms.

After a lengthy back and forth about the productivity of the cows and price structures, John asked “What is reality?” implying that Putin might not be in touch with the actual statistics of his country.

Putin assured him that he had the facts and would be reducing the interest on loans but his more compelling conclusion he imparted to John was, “well, you must have liked doing this and it didn’t go bust after all these years” — after first saying in French “Cherchez le femme” (“Look for the woman”) as an explanation for John’s immigration to Russia — he married a Russian woman. In other words, love and family were more important than profits, a contrast between “heart” and “head” that Putin also made in debating former finance minister Aleksey Kudrin. But how was a break-even operation supposed to pay the interest on farmers’ loans that Putin’s banker friends were happy to charge?

The reality that John didn’t discuss is the continued subsidies of large parts of the population for things like milk prices and the continued inefficacy of these policies – especially when they are implemented where, as another farmer in Kostroma pointed out to Putin, middlemen make a profit from handling sales and the farmers themselves are unable to establish their own direct sales relationships with institutions like schools or hospitals that might buy milk in bulk. And the huge deficit that the Russian regions have racked up trying to make good on Putin’s populist promises from his elections isn’t addressed. Putin’s response was to blame Belarus for flooding the Russian market with cheap powdered milk.

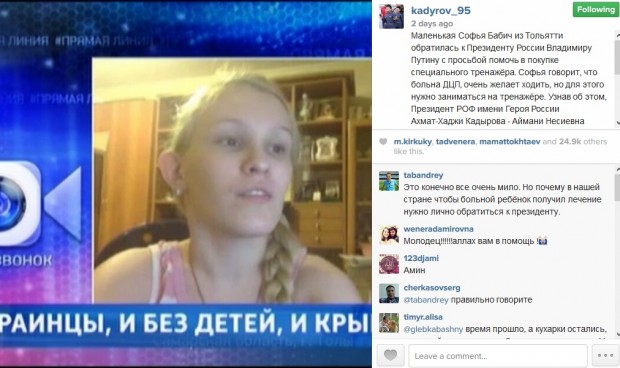

Through publicizing her plight on the call-in show, a young Russian girl with cerebral palsy was given a fitness machine to help her learn to walk by none other than Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and another happy story is projected to the audience. But behind the message of magnanimity we are left with questions – how could the Russian system allow a disabled child not be helped to walk for so many years? Why are all the foreign charities kicked out of Russia that might have helped long ago?

Девочка с ДЦП из Тольятти: Мечтаю пожать руку Путину http://t.co/OBJ3PRb3FS pic.twitter.com/E4IO4dCv80

— LIFENEWS (@lifenews_ru) April 16, 2015

Translation: A girl from Togliatti with cerebral palsy: I dream of shaking Putin’s hand.

Instagram post April 16 by Ramzan Kadyrov about organizing the gift of a fitness machine to help Sofya Babich learn to walk. A reader asks why it was necessary for a disabled child to appeal to the president to get help.

For every “reality” seemingly affirmed by the hard questions and partial answers, we can think of many other “realities” to counter with. But the space where that challenge could take place – outside the state TV and outside the controlled parliament – has increasingly shrunk in Russia under Putin’s rule.