Welcome to our column, Russia Update, where we will be closely following day-to-day developments in Russia, including the Russian government’s foreign and domestic policies.

The previous issue is here, and see also our Russia This Week feature on disarray in the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy shop; ‘Managed Spring’: How Moscow Parted Easily with the ‘Novorossiya’ Leaders and Putin ‘The Imperialist’ A Runner-Up For Time’s ‘Person of the Year’

Google announced it was withdrawing engineers from Russia today, and Skype transferred a number of programmers to Prague. The moves follow new Russian legislation requiring Western Internet companies to place Russian customers’ data on servers located on Russian soil.

Please help The Interpreter to continue providing this valuable information service by making a donation towards our costsâ€.

UPDATES BELOW

Today, December 12, the Kirovsky District Court of St. Petersburg sentenced two computer professionals for setting fire to a dormitory for labor migrants, Fontaka.ru reported.

Nikolai Antipanov, 30, a programmer, and Aleksey Konyakhin, 24, an engineer, threw Molotov cocktails at the Ekonom dormitory last April, grani.ru reported.

Judge Yuliya Romanova re-qualified the arson as “deliberate cause of harm to health” under Russian law, rather than “attempted murder.”

Prosecutors had requested 10 and 9 years of strict-regimen labor camp for the two, but the judge reduced this to 6 years standard-regimen for Antipanov and 5 years for Konyakhin.

The arsonists’ attack on the migrants was one of a number of violent attacks on produce sellers in St. Petersburg’s markets who come from Russia’s North Caucasus or Central Asia.

See: Blonde with a Bat: An Anti-Immigrant Pogrom

Moscow has also been the site of assaults on migrants, such as the burning of the vegetable warehouse in Biryulyovo.

See: ‘Their Brains are Like a Wrecking Ball: Analysis of Moscow’s Race Riots.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick

Yesterday December 11 at a news conference in Moscow, attackers threw eggs on human rights advocates trying to publicize concerns about the collective punishment measures imposed by Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. As we reported, Kadyrov ordered the houses of relatives terrorists killed in the police gunfight in Grozny on December 4 to be burned down, saying he had lost a relative of his own when the 11 policemen were killed.

The human rights press conference featured Igor Kalyapin of the Joint Mobile Group of Russian human rights defenders in Chechnya, Aleksandr Cherkassov of Memorial Society Human Rights Center, and Tanya Lokshina of Human Rights Watch’s office in Moscow. Lokshina published an account of the attack on the organization’s website:

While Igor was speaking, one man got up and demanded to ask a

question. I said he had to wait until the end of the speakers’

statements. He insisted. I asked him to sit down. He started shouting

and moving toward the speakers’ table. The two men behind him also

jumped up, yelling some incoherent accusations and rushed toward us.

For a second, I thought they’d spray us with pepper gas or something

worse, so when they started throwing eggs I felt almost relieved. They

aimed at Kalyapin, and as they were literally two steps away from him,

they easily hit their target. Kalyapin’s suit was ruined and his hair

was a gooey mess. Another colleague and I also got splattered, and a

particularly fat blob of raw egg landed on top of my last copy of Human

Rights Watch’s 2009 report about punitive house burnings in Chechnya.

Activists took a video of the news conference, where Kalyapin is shown calmly describing his concerns about the legality of the Chechen president’s actions when two men jump up and begin shouting their support of Kadyrov and asking if Human Rights Watch had a solution to terrorism, given that policemen were killed.

At the end, Aleksandr Cherkassov, head of the Human Rights Center of Memorial Society stands up and says indignantly to the men, “Vy — yaitsa poteryali,” which in Russian is a double entendre which means both “You have lost your eggs” and “You have lost your balls,” a reference to the cowardly move by the Kadyrov provocateurs.

The activists decided to continue their press conference without even cleaning up the eggs.

Memorial’s Human Rights Center as well as its national Russian organization have been declared by the Ministry of Justice “foreign agents” under a new law restricting NGOs and have repeatedly appealed the rulings.

Memorial’s Yelena Zhemkova announced that the organization had notified the Justice Ministry of changes to their charter, Interfax reported.

The group had succeeded in getting a court hearing scheduled for November postponed to December 17 to enable members to convene a congress and make changes to their charter specifying the relationship between the national and local chapters of Memorial. Under the new charter, International Memorial Society became a union of organizations, and Russian Memorial Society became an association of physical persons.

Ella Pamfilova, the Russian ombudsperson for human rights, and Mikhail Fedotov, chairman of the Presidential Council on Human Rights, have spoken out in defense of Memorial Society, the leading independent human rights organization on Russia.

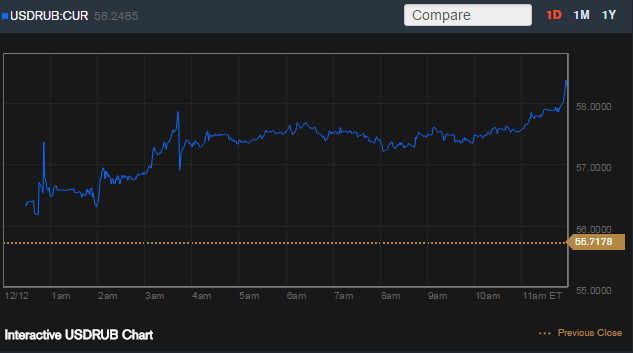

Bloomberg reports that as of 11:59 ET today, the ruble was trading at 58.2805 to the USD, a drop of 4.6%. A look at just today’s graph shows that at almost no point did that rate look like it was going to improve:

Once again, the exchange rate for the ruble is actually falling at a greater rate than the price of oil. WTI crude oil traded at $57.70 per barrel today, a drop of 3.75%. And if you’re paying attention, the joke about Putin being 63 years old doesn’t work any more. Even Brent crude oil is trading at $61.70 per barrel. The reality of Russia’s current economic environment is worse than a bad joke.

But The Economist asks the crucial question — how much does Russia have in foreign-exchange reserves?

The central bank has also been buying roubles with its foreign-exchange reserves. They have fallen sharply this year (nearly 20%) but still seem gargantuan. According to the central-bank website, in November Russia had $419 billion-worth of reserves. Even after this year’s drop, only a handful of countries have bigger reserves than Russia.

But Russia’s official figures do not tell the whole story. About $170 billion of its assets sit in two big wealth funds, the Reserve Fund (worth about $89 billion) and the National Wealth Fund (worth about $82 billion). But much of what is in these funds could prove inaccessible if called on to meet short-term financing needs.

In other words, Russia may not be on the verge of collapse, not by a long shot, but may not have liquid assets. At the end of the day, however, The Economist concedes that no one really knows how much Russia has in reserve.

Either way, Bloomberg argues that there is very little that Russia’s central bank can do to fix the slumping currency:

“Any attempt to curb the selloff in the ruble is going to do more damage than good,” Christensen, the bank’s Copenhagen-based chief emerging-markets economist, said by phone yesterday. “We can all fear that something more desperate will be done to stabilize the currency, such as capital controls.”

Norway is suspending bilateral military activities with Russia until the end of 2015, the Norwegian Ministry of Defence announced on its web site today:

Military bilateral cooperation has been suspended since March 2014, since the illegal annexation of Crimea and destabilization in eastern Ukraine. The Government has considered the issue again and decided to continue the suspension of all bilateral military activities until the end of 2015.

“The situation in Eastern Ukraine is serious, and Russia has indisputably a destabilizing role. Russia supports separatists in eastern Ukraine military and military forces along the border. This is not acceptable,” says Defence Minster Ine Eriksen Søreide.

The defence minister said cooperation would continue by the Coast Guard, Border Guard as well as under the Incidents at Sea Agreement for the sake of search-and-rescue activities Contact between the Norwegian Joint Headquarters and the Northern Fleet would continue for security reasons as well.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick

Google is removing is engineering and technical services from Russia, Financial Times, Vedomosti, and other media have reported.

Google would not confirm the move when asked by Moscow Times, but Bloomberg has quoted a source which said Google was transferring engineering operations following the new law requiring local storage of customers data. Google has stressed in conjunction with the announcement that it will continue to serve Russia:

“We are deeply committed to our Russian users and customers,” Google

said in a statement. “We have a dedicated team in Russia working to

support them.”

The tech blog The Information quoted a source inside Google

that said the company plans to find jobs in their other offices around

the world for about 50 Russian software developers whom they will now

have to fire, Fortune.com reported.

While Google has not discussed it publicly, the move is seen by Western journalists as dictated by a new Russian law set to go into effect next year that requires foreign Internet Service Providers to place Russian customer data on servers on Russian territory. The withdrawal comes “amid Kremlin crackdown on web freedom and Internet companies,” says the Wall Street Journal in a sub-headline.

Russian officials have threatened Western companies with blocking of their Internet sites if they do not comply with Russian law. Other new Internet laws enable further access of Russian intelligence to customer communications, registration of users at Internet cafes, and further control over bloggers.

Wired reported on “Russia’s Creeping Descent into Internet Censorship,” citing Andrei Soldatov, a journalist who specializes in Internet and intelligence issues, regarding the implications for Western companies in Russia:

If their servers are in Russia, that would

mean even stricter censorship for U.S. companies. But, as Soldatov

explains, it would also open these companies to surveillance by Russia’s ederal Security Service, known as the FSB. The more likely outcome is

that, if Russia clamps down on U.S. companies, some just won’t play in

the country. Indeed, the Wall Street Journal described

the situation as a “near-impossible challenge for US-based firms that

have millions of Russian users but generally store data on servers

outside the country.”

The State Duma’s Committee on Information Policy announced that it would like to postpone the date the law is to go into effect from January 2015 to September 2015 to give more time for companies to comply, Therunet.com reported, citing TASS.

Earlier, at the urging of Vadim Dengin, a deputy from the ill-named Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, the date was moved from September 2016 to January 2015 “in the interests of national security.” Russian officials have invoked the specter of NSA surveillance as a reason to protect their data, while remaining silent on the already-existing massive surveillance of citizens’ communications by the Federal Security Service (FSB). Says Therun.et, a site covering Internet policy in Russia (translation of The Interpreter):

“Most likely this was done because the majority of companies have not managed to transfer the data of Russian users to Russia. Moreover, many statutes of the law remain unclear and require work.”

American companies Google, Facebook, Twitter and others have been in talks with Russian officials over trying to accommodate the demands, ever since the law was announced after the fugitive NSA contractor Edward Snowden sought refuge in Russia in 2013.

But these companies don’t place servers in large numbers of countries where their customers are located; they maintain large data centers in only relatively few locations. Google, for example, has such centers in the US, Chile, Taiwan, Singapore, Finland, Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands that server various parts of the world.

Google is one of the leading tech companies in Russia with its percentage of the search market rising from 27 to 31% in the last year, as Yandex fell from 62% to 60%, says Bloomberg. President Vladimir Putin cast suspicion on Yandex for having foreign board members in a speech in which he blasted the Internet as a “CIA creation.” Yandex stock fell dramatically and millions of dollars were lost, although it slowly recovered in recent months.

Google Android is also reported to have 85% of the Russian market for mobile phone operating systems. Apple has come in for a beating this year as anti-gay politicians have urged boycotting the company’s phones and other products because its CEO Tim Cook announced he was gay this year.

In September, The Information ran an article titled “There’s a Crisis Happening in the Russian Tech Industry” describing Accel and other companies divesting in Russia.

In November, Skype, originally an Estonian company purchased by Microsoft, announced it was moving some of its Russian developers formerly located in the suburb of Zelenograd to Prague, Vedomosti reported, citing a Microsoft press conference in Moscow.

Aleksandra Parisheva, Moscow representative in Russia, said Skype never had its own office in Russia, but did have a development team, and implied that the move was part of a consolidation of international R&D centers “to raise effectiveness” and eliminate communication obstacles like different time zones.

About 100 programmers worked in the Russian office, and about a third of these have agreed to move to Prague; others got a severance package of six months’ pay, she added. She did not give the exact number of developers as distinct from programmers.

Adobe Systems shut down its Russian offices in September, said Fortune.

According to Bloomberg’s source, “Google has made similar internal changes in other countries, including Sweden, Finland and Norway.”

Others in the debate have wanted to spin this as a reaction to Western surveillance.

Yet this is misleading, because the Russian demands are far greater than those of Norway.

Norway,

which is not a member of the EU, still keeps to similar personal data

and privacy legislation. In dealing with Google and other companies, it

has required segregation of data and access to it so that protection of data can be monitored, but has not made a demand literally to house servers on its territory, except for health

data, which is required to be maintained locally.

The Norwegian Data

Protection Commission director Bjorn Erik Thon said in 2012 that Google agreed to segregate data and store it “only in the EU or the

US,” indicating the issue wasn’t domestic storage. To be sure, this

interview was made before the Snowden revelations but subsequent

legislation sought to find a balance between privacy and cross-border

crime fighting. European countries have also increasingly turned to encryption in the

cloud to protect privacy.

The EU also has the Data Retention Directive requiring the storage of electronic communications for a minimum of 6

months but no more than on year, and also requiring access to police and

security agencies. The difference between these countries and Russia, which passed a similar law this year, is

that they have independent bars, judiciary systems, media and parliaments that

can serve as a check and balance against government overreach; in fact

the Court of Justice of the EU declared the directive invalid in

response to a case brought by Digital Rights Ireland against Irish

authorities on privacy grounds.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick