Among Russian politicians who had already established relations with the Western far right in the 1990s, Sergey Glazyev, currently an adviser to Russian President Vladimir Putin on the issues of regional economic integration, is one of the most prominent.

In 1992-1993, Glazyev was Minister of External Economic Relations of the Russian Federation, but resigned in protest over the decision of contemporary president Boris Yeltsin to dissolve the State Duma (Russian parliament) – the decision that resulted in the unsuccessful coup attempt staged by then vice president Aleksandr Rutskoy and then chairman of the Duma Ruslan Khasbulatov in October 1993 in Moscow. Glazyev was elected to the Duma in 1994 and became the chairman of the parliamentary Economic Affairs Committee.

Around this time, Glazyev forged relationships with Lyndon LaRouche, a US-based political activist and founder of the LaRouche movement. Chip Berlet and Matthew Nemiroff Lyons describe LaRouche and his movement as follows:

Though often dismissed as a bizarre political cult, the LaRouche organization and its various front groups are a fascist movement whose pronouncements echo elements of Nazi ideology. […] [The LaRouchites] advocated a dictatorship in which a “humanist” elite would rule on behalf of industrial capitalists. They developed an idiosyncratic, coded variation on the Illuminati Freemason and Jewish banker conspiracy theories.

As Leonard Weinberg argued, LaRouche’s ideology involved “a theory according to which a global Anglo-Jewish conspiracy exists to weaken Western society, in the face of Soviet subversion, and makes possible its control by international bankers, drug merchants, and Zionists”. In the 1970-80s, the LaRouchites were highly critical of the Soviet Union and believed that it was controlled by the British oligarchs. Indeed, Britain was often vilified by the LaRouchites: in particular, they claimed that “British royal family (including the Queen) controlled global drug running”, while the “British oligarchy” was preparing to balkanize the US. They attacked the Soviet Union too, accusing it of dictatorial and imperialist practices, and specifically focused on the Russian Orthodox Church that the LaRouchites condemned for helping the Kremlin leadership in building the “worldwide imperial hegemony, the ‘Third and Final Rome’”.

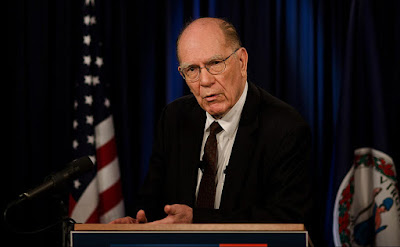

|

| Lyndon LaRouche |

With the demise of the Soviet Union, however, the LaRouchites’ attitude towards Russia gradually changed and LaRouche became genuinely interested in Russia and its economy, arguing against adoption of Western liberal economic models by Russia. In 1992, the Schiller Institute for Science and Culture was established in Moscow as a Russian branch of the LaRouchite international Schiller Institute, and started publishing Russian translations of LaRouche’s essays.

Glazyev and LaRouche most likely met in person for the first time in April 1994, when LaRouche and his wife and associate Helga Zepp-LaRouche travelled to Russia and addressed a number of workshops, including one at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. Glazyev’s senior colleague, late Russian economist Dmitry Lvov who was in contact with LaRouche too, was a full member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and might be one of the people who officially invited LaRouche to Moscow. Late Taras Muranivsky, professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities and president of the Russian branch of the Schiller Institute, might also be involved in organising LaRouche’s visit to Moscow.

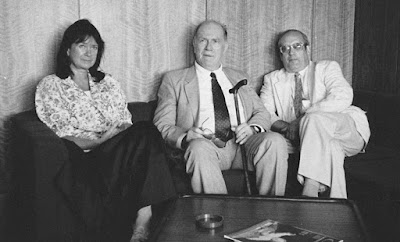

|

| Helga Zepp-LaRouche, Lyndon LaRouche, and Dmitriy Lvov, Moscow, 1995 |

LaRouche’s contacts in Russian academia and the Moscow-based Schiller Institute for Science and Culture actively promoted his ideas in Russia, and, since 1995, he has been trying to exert direct influence on Russian policy-making in the economic sphere. Representatives of the Schiller Institute for Science and Culture presented LaRouche’s memorandum “Prospects for Russian Economic Revival” at the State Duma, while later that year LaRouche himself appeared in the Russian parliament to present his report “The World Financial System and Problems of Economic Growth”. His conspiracy-driven economic theories that denounced free trade and commended protectionism, as well as attacking the workings of the International Monetary Fund, stroke a chord with many a member of the Duma largely dominated by the anti-liberal and anti-democratic forces such as the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia and other ultranationalists.

During the 1990s, the LaRouchites praised Glazyev as “a leading economist of the opposition to Boris Yeltsin’s regime” and published Glazyev’s interviews and articles in their weekly Executive Intelligence Review. In 1999, LaRouche published an English translation of Glazyev’s book Genocide: Russia and the New World Order in which the author exposed his theories about “the world oligarchy” using “depopulation techniques developed by the fascists” “to cleanse the economic space of Russia for international capital”. According to Glazyev, the US – under the guidance of “the world oligarchy” – is implementing “anti-Russian policies” aimed at preventing “the reunification of the Russian people”, provoking “further dismemberment of Russia” and frustrating “integration processes within the territory of the CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States]”.

On the part of LaRouche, his interest in Russia and cooperation with Glazyev were driven by practical considerations. LaRouche’s grand idea in relation to Russia was that of a “Eurasian land-bridge” between Western and Eastern parts of Eurasia, a project that, according to LaRouche, the US would be interested in and to which Russia would “supply a crucial contributing role”. While LaRouche’s Russian associates might not share his views on the national interests of the US in the framework of the “Eurasian land-bridge” concept, they embraced his populist interpretation of the economic situation in Russia that he described as one that was characterized by a conflict between

the imported liberalism of those “chop-shop entrepreneurs” who stuff their own purse with money from foreign sales of national assets at stolen-goods prices, and Russians of more patriotic inclinations, notably those whose overriding commitment, as professionals, is to filling the barren, physical-economic market-baskets of their perilously hungered countrymen.

The relations between LaRouche and Glazyev continued in the 2000s, the Putin era. In particular, LaRouche and Helga Zepp-LaRouche took part in the Duma hearing “On Measures to Ensure the Development of the Russian Economy under Conditions of a Destabilization of the World Financial System” held in June 2001 at the initiative of Glazyev who was then chairman of the Duma Committee on Economic Policy and Entrepreneurship.

|

| A press conference: Lyndon LaRouche, Helga-Zepp LaRouche, and Sergey Glazyev, Moscow, June 2001 |

Glazyev’s promotion of LaRouche and his ideas in Russia resulted in the latter’s growth in popularity as an opinion-maker and commentator on political and economic issues in Russia – a status that LaRouche could not enjoy in his home country where he has remained a fringe political figure.